Ilocano language

Iloco (also Ilóko, Ilúko, Ilocáno or Ilokáno; /iːloʊˈkɑːnoʊ/;[6] Iloco: Pagsasaó nga Ilóko) is an Austronesian language primarily spoken in the Philippines by the Ilocano people.[7][8] It is one of the eight major languages of the Philippines with about 11 million speakers and ranks as the third most widely spoken native language.[9][10] Iloco serves as a regional lingua franca and second language among Filipinos in Northern Luzon, particularly among the Cordilleran (Igorot) ethnolinguistic groups, as well as in parts of Cagayan Valley and some areas of Central Luzon.[11][12] As an Austronesian language, Iloco or Ilocano shares linguistic ties with other Philippine languages and is related to languages such as Indonesian, Malay, Tetum, Chamorro, Fijian, Māori, Hawaiian, Samoan, Tahitian, Paiwan, and Malagasy.[11] It is closely related to other Northern Luzon languages and exhibits a degree of mutual intelligibility with Balangao language and certain eastern dialects of Bontoc language.[13][14] Iloco is also spoken outside of Luzon, including in Mindoro, Palawan, Mindanao, and internationally in Canada, Hawaii and California in the United States, owing to the extensive Ilocano diaspora in the 19th and 20th centuries.[15][16] About 85% of the Filipinos in Hawaii are Ilocano and the largest Asian ancestry group in Hawaii.[17] In 2012, it was officially recognized as the provincial language of La Union, underscoring its cultural and linguistic significance.[18][19] The Ilocano people historically utilized an indigenous writing system known as kur-itan. There have been proposals to revive this script by incorporating its instruction in public and private schools within Ilocos Norte and Ilocos Sur, where Ilocano is predominantly spoken.[20] EtymologyIn early history, the Ilocano people referred to themselves as "Samtoy," a term derived from the Iloco phrase sao mi ditoy, meaning "our language." [21] The term "Ilocano" originates from the native word "Ilúko" and has undergone linguistic evolution influenced by both indigenous and Spanish elements. It is derived from the Ilocano prefix i-, meaning "of" or "from," combined with luék, luëk, or loóc, which denote "sea" or "bay." This etymology suggests that the language, like the people, was historically associated with coastal settlements, thus signifying "language of the people from the bay." [22] An alternative linguistic interpretation connects the term to the Ilocano words lúku or lúkung, which refer to flatlands, valleys, or low-lying areas. According to this explanation, "Ilocano" may have originally meant "language of the people of the lowlands," distinguishing it from the languages spoken by mountain-dwelling communities.[23] During Spanish colonization, the term "Ilocano" was formalized and adapted to Spanish linguistic conventions. The suffix -ano, commonly used in Spanish to denote a group or people (as seen in terms such as Americano or Mexicano), was appended to align with Spanish grammatical structures. This adaptation contributed to the term’s official recognition and widespread use in colonial records and classifications. Classification The Ilocano language, also known as Iloco, belongs to the Austronesian language family, specifically within the Malayo-Polynesian branch. It is widely believed to have originated in Taiwan through the "Out of Taiwan" migration theory. This theory, proposed by archaeologist Peter Bellwood, posits that the Philippines was populated by Austronesian-speaking people who migrated from Taiwan around 3,000 BCE.[24][25]  Ilocano constitutes its own branch within the Philippine Cordilleran subfamily, which is part of the larger Northern Luzon languages. It is spoken as a first language by approximately eight million people. Linguist Lawrence Reid, an expert in Austronesian languages, categorizes over thirty Northern Luzon languages into five main branches: Northeastern Luzon, Cagayan Valley, Meso-Cordilleran, with Ilocano (Iloco) and Arta further classified as group-level isolates.[26] Serving as a lingua franca for much of Northern Luzon and parts of Central Luzon, Ilocano is also spoken as a second language by over two million individuals. These speakers include native speakers of languages such as Ibanag, Itawes, Ivatan, Bolinao, Pangasinan, Sambal, and other regional languages.[2] Geographic distributionThe Iloco language is primarily spoken in Northern Luzon with 8.7 million native speakers and about 2 million as second language,[2] where the highest concentration of Iloco speakers remains in their home provinces in Ilocos Region, totaling approximately three million. As of the 2020 census, Iloco speakers account for 5.8% of the Philippine population, or 3,083,391 individuals, with the majority residing in the Ilocos Region. The province of Pangasinan has the largest number of Iloco speakers, at 1,258,746, followed by La Union with 673,312, Ilocos Sur with 580,484, and Ilocos Norte with 570,849.[27] Ilocano-speaking density across provinces. Enlarge for detailed percent distribution. Areas where Iloco is the majority language, highlighting regions with the highest concentration of speakers. Map of the areas where Ilocano is the majority native language. In Cagayan Valley, Iloco speakers number 2,274,435, representing 61.8% of the region’s population. Isabela has the highest number of Iloco speakers at 1,074,212, followed by Cagayan with 820,546, Nueva Vizcaya with 261,901, Quirino with 117,360, and Batanes with 416. In the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR), where Iloco serves as a lingua franca among the Cordilleran (Igorot) people, the number of Iloco speakers totals 396,713, comprising 22.1% of the region’s population. The province of Abra, formerly part of the Ilocos Region, has the highest number of Iloco speakers at 145,492, followed by Benguet (including Baguio City) with 138,022, Apayao with 47,547, Kalinga with 31,812, Ifugao with 26,677, and Mountain Province with 7,163 Iloco speakers.[27] Outside of Northern Luzon, Central Luzon is home to 10.8% of Iloco speakers, or 1,335,283 individuals. In Tarlac, 555,000 Iloco speakers were recorded, followed by Nueva Ecija with 369,864, Zambales (including Olongapo City) with 183,629, Bulacan with 97,603, Aurora with 65,204, Pampanga (including Angeles City) with 40,862, and Bataan with 29,121. In the National Capital Region (NCR), 762,629 Iloco speakers were documented, while CALABARZON has 330,774 Iloco speakers, and MIMAROPA (with a majority in Mindoro and Palawan) has 117,635. In the Bicol Region, there are 15,434 Iloco speakers.[27] In the Visayas, there are 13,079 Iloco speakers, and in Mindanao, the number reaches 416,796. The SOCCSKSARGEN region in Mindanao has the highest concentration of Iloco speakers, with 248,033, the majority of whom reside in Sultan Kudarat (97,983).[27] Internationally, Iloco is spoken in the United States, with the largest concentrations in Hawaii and California,[15] as well as in Canada.[28] In Hawaii, 17% of those who speak a non-English language at home speak Iloco, making it the most spoken non-English language in the state.[16] In September 2012, the province of La Union became the first in the Philippines to pass an ordinance recognizing Ilocano (Iloko) as an official provincial language, alongside Filipino and English. This ordinance aims to protect and revitalize the Ilocano language, although other languages, such as Pangasinan, Kankanaey, and Ibaloi, are also spoken in La Union.[18][5] Writing systemModern alphabetThe modern Ilokano alphabet consists of 29 letters:[29] Aa, Bb, Cc, Dd, Ee, Ff, Gg, Hh, Ii, Jj, Kk, Ll, LLll, Mm, Nn, Ññ, NGng, Oo, Pp, Qq, Rr, Ss, Tt, Uu, Vv, Ww, Xx, Yy, and Zz Pre-colonial Pre-colonial Ilocano people of all classes wrote in a syllabic system known as Baybayin prior to European arrival. They used a system that is termed as an abugida, or an alphasyllabary. It was similar to the Tagalog and Pangasinan scripts, where each character represented a consonant-vowel, or CV, sequence. The Ilocano version, however, was the first to designate coda consonants with a diacritic mark – a cross or virama – shown in the Doctrina Cristiana of 1621, one of the earliest surviving Ilokano publications. Before the addition of the virama, writers had no way to designate coda consonants. The reader, on the other hand, had to guess whether a consonant not succeeding a vowel is read or not, for it is not written. Vowel apostrophes interchange between e or i, and o or u. Due to this, the vowels e and i are interchangeable, and letters o and u, for instance, tendera and tindira ('shop-assistant'). Modern In recent times, there have been two systems in use: the Spanish system and the Tagalog system. In the Spanish system words of Spanish origin kept their spellings. Native words, on the other hand, conformed to the Spanish rules of spelling. Most older generations of Ilocanos use the Spanish system. In the alphabet system based on that of Tagalog there is more of a phoneme-to-letter correspondence, which better reflects the actual pronunciation of the word.[a] The letters ng constitute a digraph and count as a single letter, following n in alphabetization. As a result, numo ('humility') appears before ngalngal ('to chew') in newer dictionaries. Words of foreign origin, most notably those from Spanish, need to be changed in spelling to better reflect Ilocano phonology. Words of English origin may or may not conform to this orthography. A prime example using this system is the weekly magazine Bannawag. Samples of the two systemsThe following are two versions of the Lord's Prayer. The one on the left is written using Spanish-based orthography, while the one on the right uses the Tagalog-based system.

Comparison between the two systems

Notes 1. In Ilocano phonology, the labiodental fricative sound /f/ does not exist. Its approximate sound is /p/. Therefore, in words of Spanish or English origin, /f/ becomes /p/. In particular (yet not always the case), last names beginning with /f/ are often said with /p/, for example Fernández /per.'nan.des/.2. The sound /h/ only occurs in loanwords, and in the negative variant haan.

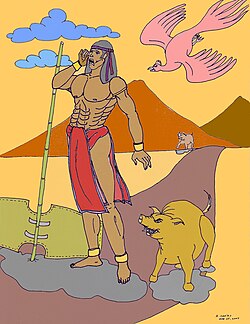

EducationHistorically, with the implementation by the Spanish of the Bilingual Education System of 1897, Ilocano, together with the other seven major languages (those that have at least a million speakers), was allowed to be used as a medium of instruction until the second grade. It is recognized by the Commission on the Filipino Language as one of the major languages of the Philippines.[30] Constitutionally, Ilocano is an auxiliary official language in the regions where it is spoken and serves as auxiliary media of instruction therein.[31] In 2009, the Department of Education instituted Department Order No. 74, s. 2009 stipulating that "mother tongue-based multilingual education" would be implemented. In 2012, Department Order No. 16, s. 2012 stipulated that the mother tongue-based multilingual system was to be implemented for Kindergarten to Grade 3 Effective School Year 2012–2013.[32] Ilocano is used in public schools mostly in the Ilocos Region and the Cordilleras. It is the primary medium of instruction from Kindergarten to Grade 3 (except for the Filipino and English subjects) and is also a separate subject from Grade 1 to Grade 3. Thereafter, English and Filipino are introduced as mediums of instruction. Literature Ilocano literature traces its origins to the animistic past of the Ilocano people. Key narratives include creation myths featuring figures such as Aran, Angalo, and Namarsua, the Creator, alongside tales of benevolent and malevolent spirits.  Ancient Ilocano poets articulated their expressions through folk and war songs, as well as the dállot, an improvised long poem delivered in a melodic manner. A significant work within this literary tradition is the epic Biag ni Lam-ang (The Life of Lam-ang), which is one of the few indigenous narratives that have survived colonial influence. Ilocano culture is further celebrated through life rituals, festivities, and oral traditions, expressed in songs (kankanta), dances (salsala), poems (dandániw), proverbs (pagsasao), and literary duels (bucanegan), which all preserve Ilocano identity and demonstrate its adaptability within the evolving Filipino cultural landscape.  During the Spanish regime, Iloco poetry was heavily influenced by Spanish literary forms, with the earliest written Iloco poems largely based on romances translated from Spanish by Francisco Lopez. In 1621, Lopez published the Doctrina Christiana, the first book printed in Iloco. The 17th-century author Pedro Bucaneg, known for his collaboration with Lopez on the Doctrina, is celebrated as the "Father of Ilocano Poetry and Literature, credited for composing the epic poem Biag ni Lam-ang ("Life of Lam-ang"), which narrates the adventures of the Ilocano hero Lam-ang. A study of Iloco poetry can also be found in the Gramatica Ilokana, published in 1895, which is based on Lopez's earlier work, Arte de la Lengua Iloca, published in 1627 but likely written before 1606.  In the 18th century, missionaries became involved in promoting literacy and religious education among the Ilocano population through the publication of religious and secular texts, including Sumario de las Indulgencias de la Santa Correa by Jacinto Rivera and a translation of St. Vincent Ferrer's sermons by Antonio Mejia. The 19th century witnessed the rise of Leona Florentino, who has been recognized as the National Poetess of the Philippines, although her sentimental poetry received criticism from modern readers for lacking depth and structure. The early 20th century brought forth notable Ilocano writers such as Manuel Arguilla, who was a guerrilla fighter during World War II, and Carlos Bulosan who authored the novel America Is in the Heart. Other distinguished writers from this period include Sionil Jose, known for his epic sagas set in Pangasinan, and Isabelo de los Reyes, who was involved in preserving and publishing Ilocano literary works, including the earliest known text of Biag ni Lam-ang. PhonologySegmentalVowelsWhile there is no official dialectology for Ilocano, the usually agreed dialects of Ilocano are two, which are differentiated only by the way the letter e is pronounced. In the Amiánan (Northern) dialect, there exist only five vowels while the older Abagátan (Southern) dialect employs six.[7]

Reduplicate vowels are voiced separately with an intervening glottal stop:

The letter in bold is the graphic (written) representation of the vowel.

For a better rendition of vowel distribution, please refer to the IPA Vowel Chart. Unstressed /a/ is pronounced [ɐ] in all positions except final syllables, like madí [mɐˈdi] ('cannot be') but ngiwat ('mouth') is pronounced [ˈŋiwat]. Unstressed /a/ in final-syllables is mostly pronounced [ɐ] across word boundaries. Although the modern (Tagalog) writing system is largely phonetic, there are some notable conventions. O/U and I/EIn native morphemes, the close back rounded vowel /u/ is written differently depending on the syllable. If the vowel occurs in the ultima of the morpheme, it is written o; elsewhere, u. Example:

Instances such as masapulmonto, 'You will manage to find it, to need it', are still consistent. Note that masapulmonto is, in fact, three morphemes: masapul (verb base), -mo (pronoun) and -(n)to (future particle). An exception to this rule, however, is laud /la.ʔud/ ('west'). Also, u in final stressed syllables can be pronounced [o], like [dɐ.ˈnom] for danum ('water'). The two vowels are not highly differentiated in native words due to fact that /o/ was an allophone of /u/ in the history of the language. In words of foreign origin, notably Spanish, they are phonemic. Example: uso 'use'; oso 'bear' Unlike u and o, i and e are not allophones, but i in final stressed syllables in words ending in consonants can be [ɛ], like ubíng [ʊ.ˈbɛŋ] ('child'). The two closed vowels become glides when followed by another vowel. The close back rounded vowel /u/ becomes [w] before another vowel; and the close front unrounded vowel /i/, [j]. Example: kuarta /kwaɾ.ta/ 'money'; paria /paɾ.ja/ 'bitter melon' In addition, dental/alveolar consonants become palatalized before /i/. (See Consonants below). Unstressed /i/ and /u/ are pronounced [ɪ] and [ʊ] except in final syllables, like pintás ('beauty') [pɪn.ˈtas] and buténg ('fear') [bʊ.ˈtɛŋ, bʊ.ˈtɯŋ] but bangir ('other side') and parabur ('grace/blessing') are pronounced [ˈba.ŋiɾ] and [pɐ.ˈɾa.buɾ]. Unstressed /i/ and /u/ in final syllables are mostly pronounced [ɪ] and [ʊ] across word boundaries. Pronunciation of ⟨e⟩The letter ⟨e⟩ represents two vowels in the non-nuclear dialects (areas outside the Ilocos provinces) [ɛ ~ e] in words of foreign origin and [ɯ] in native words, and only one in the nuclear dialects of the Ilocos provinces, [ɛ ~ e].

DiphthongsDiphthongs are combination of a vowel and /i/ or /u/. In the orthography, the secondary vowels (underlying /i/ or /u/) are written with their corresponding glide, y or w, respectively. Of all the possible combinations, only /aj/ or /ej/, /iw/, /aw/ and /uj/ occur. In the orthography, vowels in sequence such as uo and ai, do not coalesce into a diphthong, rather, they are pronounced with an intervening glottal stop, for example, buok 'hair' /bʊ.ʔok/ and dait 'sew' /da.ʔit/.

The diphthong /ei/ is a variant of /ai/ in native words. Other occurrences are in words of Spanish and English origin. Examples are reyna /ˈɾei.na/ (from Spanish reina, 'queen') and treyner /ˈtɾei.nɛɾ/ ('trainer'). The diphthongs /oi/ and /ui/ may be interchanged since /o/ is an allophone of /u/ in final syllables. Thus, apúy ('fire') may be pronounced /ɐ.ˈpoi/ and baboy ('pig') may be pronounced /ˈba.bui/. As for the diphthong /au/, the general rule is to use /aw/ for native words while /au/ will be used for spanish loanword such as the words autoridad, autonomia, automatiko. The same rule goes to the diphthong /ai/. Consonants

All consonantal phonemes except /h, ʔ/ may be a syllable onset or coda. The phoneme /h/ is a borrowed sound (except in the negative variant haan) and rarely occurs in coda position. Although the Spanish word reloj 'clock' would have been heard as [re.loh], the final /h/ is dropped resulting in /re.lo/. However, this word also may have entered the Ilokano lexicon at early enough a time that the word was still pronounced /re.loʒ/, with the j pronounced as in French, resulting in /re.los/ in Ilokano. As a result, both /re.lo/ and /re.los/ occur. The glottal stop /ʔ/ is not permissible as coda; it can only occur as onset. Even as an onset, the glottal stop disappears in affixation. Take, for example, the root aramat [ʔɐ.ɾa.mat], 'use'. When prefixed with ag-, the expected form is *[ʔɐɡ.ʔɐ.ɾa.mat]. But, the actual form is [ʔɐ.ɡɐ.ɾa.mat]; the glottal stop disappears. In a reduplicated form, the glottal stop returns and participates in the template, CVC, agar-aramat [ʔɐ.ɡaɾ.ʔɐ.ɾa.mat]. Glottal stop /ʔ/ sometimes occurs non-phonemically in coda in words ending in vowels, but only before a pause. Stops are pronounced without aspiration. When they occur as coda, they are not released, for example, sungbat [sʊŋ.bat̚] 'answer', 'response'. Ilokano is one of the Philippine languages which is excluded from [ɾ]-[d] allophony, as /r/ in many cases is derived from a Proto-Austronesian *R; compare bago (Tagalog) and baró (Ilokano) 'new'. The language marginally has a trill [r] which is spelled as rr, for example, serrek [sɯ.ˈrɯk] 'to enter'. Trill [r] is sometimes an allophone of [ɾ] in word-initial position, syllable-final, and word-final positions, spelled as single ⟨r⟩, for example, ruar 'outside' [ɾwaɾ] ~ [rwar]. It is only pronounced flap [ɾ] in affixation and across word boundaries, especially when vowel-ending word precedes word-initial ⟨r⟩. But it is different in proper names of foreign origin, mostly Spanish, like Serrano, which is correctly pronounced [sɛ.ˈrano]. Some speakers, however, pronounce Serrano as [sɛ.ˈɾano]. ProsodyPrimary stressThe placement of primary stress is lexical in Ilocano. This results in minimal pairs such as /ˈkaː.jo/ ('wood') and /ka.ˈjo/ ('you' (plural or polite)) or /ˈkiː.ta/ ('class, type, kind') and /ki.ˈta/ ('see'). In written Ilokano the reader must rely on context, thus ⟨kayo⟩ and ⟨kita⟩. Primary stress can fall only on either the penult or the ultima of the root, as seen in the previous examples. While stress is unpredictable in Ilokano, there are notable patterns that can determine where stress will fall depending on the structures of the penult, the ultima and the origin of the word.[2]

Secondary stressSecondary stress occurs in the following environments:

Vowel lengthVowel length coincides with stressed syllables (primary or secondary) and only on open syllables except for ultimas, for example, /'ka:.jo/ 'tree' versus /ka.'jo/ (second person plural ergative pronoun). Stress shiftAs primary stress can fall only on the penult or the ultima, suffixation causes a shift in stress one syllable to the right. The vowel of open penults that result lengthen as a consequence.

Grammar

Ilocano is typified by a predicate-initial structure. Verbs and adjectives occur in the first position of the sentence, then the rest of the sentence follows. Ilocano uses a highly complex list of affixes (prefixes, suffixes, infixes and enclitics) and reduplications to indicate a wide array of grammatical categories. Learning simple root words and corresponding affixes goes a long way in forming cohesive sentences.[34] LexiconBorrowingsForeign accretion comes largely from Spanish, followed by English and smatterings of much older accretion from Hokkien (Min Nan), Arabic and Sanskrit.[35][36][37]

Common expressionsIlokano shows a T-V distinction.

Numbers, days, monthsNumbersIlocano uses two number systems, one native and the other derived from Spanish.

Ilocano uses a mixture of native and Spanish numbers. Traditionally Ilocano numbers are used for quantities and Spanish numbers for time or days and references. Examples: Spanish:

Ilocano:

Days of the weekDays of the week are directly borrowed from Spanish.

MonthsLike the days of the week, the names of the months are taken from Spanish.

Units of timeThe names of the units of time are either native or derived from Spanish. The first entries in the following table are native; the second entries are Spanish-derived.

To mention time, Ilocanos use a mixture of Spanish and Ilocano:

More Ilocano words

Also of note is the yo-yo, probably named after the Ilocano word yóyo.[38] See alsoNotes

Citations

References

External links Iloko edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Wikivoyage has a phrasebook for Ilocano.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||