Zarya (ISS module)

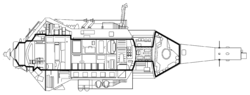

Zarya (Russian: Заря, lit. 'Sunrise'),[b] also known as the Functional Cargo Block (Russian: Функционально-грузовой блок), is the first module of the International Space Station (ISS). Launched on 20 November 1998 atop a Proton-K rocket, the module would serve as the ISS's primary source of power, propulsion, and guidance during its early years. As the ISS expanded, Zarya's role shifted primarily to storage, both internally and in its external fuel tanks.[4] A descendant of the TKS spacecraft used in the Salyut programme, Zarya was built in Russia but financed by the United States. Its name, meaning "sunrise," symbolizes the beginning of a new era of international space cooperation.[5] Construction The design of Zarya traces its heritage to the TKS spacecraft developed for the Salyut programme. The TKS consisted of two parts: the VA spacecraft, a capsule that housed cosmonauts during launch and re-entry, and the Functional Cargo Block (FGB), which contained a large pressurized cargo compartment. This arrangement allowed the VA capsule to return to Earth while leaving the FGB attached as a station module.[6] FGB modules were added to Salyut 6 and Salyut 7, and five of Mir's modules were also based on the FGB design. An FGB also served as the upper stage of the Polyus spacecraft, that failed to reach orbit on the first Energia launch in 1987.[7] Zarya itself was built between December 1994 and January 1998 at the Khrunichev State Research and Production Space Center in Moscow, funded by a US$220 million (equivalent to US$470 million in 2024) NASA contract,[8] significantly less than the alternative "Bus-1" design proposed by Lockheed Martin (US$450 million in 1994, equivalent to US$950 million in 2024). Commentators in the West noted that Zarya was completed and launched more quickly and cheaply than expected in the post-Soviet era. Some suggested that its FGB structure, like that of most Mir modules, was largely assembled from mothballed hardware originally built for the Soviet-era Skif laser weapon program, which was canceled after the loss of the first Polyus spacecraft. Under this interpretation, NASA's funding of Zarya effectively underwrote the cost of the Zvezda service module, Russia's primary early contribution to the ISS. As part of the NASA contract, Khrunichev also assembled much of a contingency flight spare, FGB-2, which was likewise believed to incorporate unused hardware. Roscosmos later funded its completion as Nauka, which launched to the ISS in 2021.[9] Design Zarya has a mass of 19,323 kilograms (42,600 lb), is 12.56 meters (41.2 ft) long, and 4.11 meters (13.5 ft) wide at its widest point. The module has three docking ports: one at the aft end (the rear of the station in its usual orientation and direction of travel) and two on a "docking sphere" at the opposite forward end, one facing forward and the other nadir (Earth-facing). A planned zenith (space-facing) port in the docking sphere was sealed with a spherical cover after a design change.[10] The forward port is attached to Pressurized Mating Adapter-1 (PMA-1), which connects to the Unity module, with PMA-1 serving as the link between the Russian Orbital Segment (ROS) and the US Orbital Segment (USOS). The aft port is connected to the Zvezda service module. The nadir port was used by a couple of visiting Progress cargo spacecraft until 2010, when the Rassvet module was docked; since then, visiting spacecraft have used Rassvet's nadir port instead.[11] For power, Zarya is equipped with two solar arrays measuring 10.67 by 3.35 meters (35 by 11 ft) and six nickel-cadmium batteries, providing an average of 3 kilowatts of power. The solar arrays have been partially retracted[12] to allow deployment of the P1/S1 radiators on the Integrated Truss Structure. While they still generate power, they no longer produce the full 3 kilowatts (4.0 hp) that was available when fully unfurled.[13] For propulsion, Zarya has 16 external fuel tanks capable of storing up to 6.1 tonnes (13,000 lb) of propellant. This capability was mandated by NASA in 1997 to ensure that the FGB could independently store and transfer propellant, even if the Zvezda Service Module was delayed.[14] Zarya is equipped with 24 large steering jets, 12 small steering jets, and two large engines previously used for reboost and major orbital maneuvers. With the docking of Zvezda, these engines were permanently disabled. The propellant tanks that once fueled Zarya’s engines are now used to store additional fuel for Zvezda. Launch and flight Zarya was launched on 20 November 1998 atop a Russian Proton-K rocket from Baikonur Cosmodrome Site 81 in Kazakhstan, into a 400-kilometer (250 mi) orbit, with a planned operational lifetime of at least 15 years. The first U.S. contribution to the ISS, the Unity module, followed on 4 December 1998 aboard STS-88. During the mission, Commander Robert Cabana maneuvered the Space Shuttle Endeavour to within 10 meters (33 ft) of Zarya, enabling Mission Specialist Nancy Currie to capture the module with the Shuttle's robotic arm and attach its forward port to Pressurized Mating Adapter-1, which was already mounted on the aft end of Unity. Astronauts Jerry Ross and James Newman then conducted two spacewalks to connect electrical and data cables between the two modules. On 10 December 1998, Cabana and Russian cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev ceremonially entered the new orbital outpost for the first time. The crew of STS-88 departed on 13 December 1998, leaving Zarya to autonomously manage the station’s power, propulsion, and guidance, a role it was originally intended to perform for only six to eight months. However, the station would remain unoccupied for nearly two years due to delays with the Russian service module, Zvezda. Before the arrival of Zvezda, the station was visited twice by the Space Shuttle for short-duration outfitting and reboost missions: STS-96 in May 1999 and STS-101 in May 2000. Zvezda was launched on 12 July 2000 and, on 26 July, automatically docked its forward port to the aft port of Zarya. Dockings

Gallery

See also

NotesReferences

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||