Science and technology in Iran

Iran has made considerable advances in science and technology through education and training, despite international sanctions in almost all aspects of research during the past 30 years.[2][3] Iran's university population swelled from 100,000 in 1979 to 4.7 million in 2016.[4] In recent years, the growth in Iran's scientific output is reported to be the fastest in the world.[5][6][7] Science in ancient and Medieval Iran (Persia)Science in Persia evolved in two main phases separated by the arrival and widespread adoption of Islam in the region. References to scientific subjects such as natural science and mathematics occur in books written in the Pahlavi languages. Ancient technology in IranThe Qanat (a water management system used for irrigation) originated in pre-Achaemenid Iran. The oldest and largest known qanat is in the Iranian city of Gonabad, which, after 2,700 years, still provides drinking and agricultural water to nearly 40,000 people.[8] Iranian philosophers and inventors may have created the first batteries (sometimes known as the Baghdad Battery) in the Parthian or Sasanian eras. Some have suggested that the batteries may have been used medicinally. Other scientists believe the batteries were used for electroplating—transferring a thin layer of metal to another metal surface—a technique still used today and the focus of a common classroom experiment.[9] However, due to the absence of electrodes on the exterior of the pot, and the lack of records of electroplating at the time, most archaeologists believe it is not a battery, and is more likely a ritual or storage object.[10][11] Windwheels were developed by the Babylonians c. 1700 BC to pump water for irrigation. The horizontal or panemone windmill first appeared in Greater Iran during the 9th century.[12][13] Mathematics

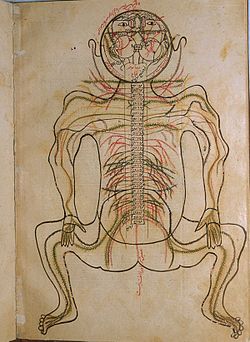

The first five rows of Khayam-Pascal's triangle The 9th century mathematician Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi founded algebra and expanded upon Persian and Indian arithmetic systems. His writings were translated into Latin by Gerard of Cremona under the title: De jebra et almucabola. Robert of Chester also translated it under the title Liber algebras et almucabala. The works of Kharazmi "exercised a profound influence on the development of mathematical thought in the medieval West".[14] The Banū Mūsā brothers ("Sons of Moses"), namely Abū Jaʿfar, Muḥammad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (before 803 – February 873), Abū al‐Qāsim, Aḥmad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th century) and Al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th century), were three 9th-century Persian[15][16] scholars who lived and worked in Baghdad. They are known for their Book of Ingenious Devices on automata and mechanical devices and their Book on the Measurement of Plane and Spherical Figures.[17] Other Iranian scientists included Abu Abbas Fazl Hatam, Farahani, Omar Ibn Farakhan, Abu Zeid Ahmad Ibn Soheil Balkhi (9th century AD), Abul Vafa Bouzjani, Abu Jaafar Khan, Bijan Ibn Rostam Kouhi, Ahmad Ibn Abdul Jalil Qomi, Bu Nasr Araghi, Abu Reyhan Birooni, the noted Iranian poet Hakim Omar Khayyam Neishaburi, Qatan Marvazi, Massoudi Ghaznavi (13th century AD), Khajeh Nassireddin Tusi, and Ghiasseddin Jamshidi Kashani. MedicineThe hospital system was developed in Sassanian Iran; for example, the Academy of Gundishapur was influential on the ideals and traditions of hospitals in the Mohammedan period.[18]   Several documents still exist from which the definitions and treatments of the headache in medieval Persia can be ascertained. These documents give detailed and precise clinical information on the different types of headaches. The medieval physicians listed various signs and symptoms, apparent causes, and hygienic and dietary rules for prevention of headaches. The medieval writings are both accurate and vivid, and they provide long lists of substances used in the treatment of headaches. Many of the approaches of physicians in medieval Persia are accepted today; however, still more of them could be of use to modern medicine.[19] During the 7th century the Achaemenian dynasty was the major advocate of science. Documents indicate that condemned criminals' bodies were dissected and used for medical research during this timeframe[20] In due course, Persians' methods of gathering scientific information would undergo a major change. In the aftermath of the conquest of Islam, Muslim armies destroyed major libraries, and as a result, Persian scholars were deeply concerned as knowledge of the fields of science had been lost. Persians also prohibited the use of human anatomical dissection by Muslim medical practitioners for social and religious reasons.[20] Persian literature was translated into Arabic for approximately two centuries to preserve the surviving Persians literature, which also indirectly served to conserve Persian history.[20] In the 10th century work of Shahnameh, Ferdowsi describes a Caesarean section performed on Rudabeh, during which a special wine agent was prepared by a Zoroastrian priest and used to produce unconsciousness for the operation.[21] Although largely mythical in content, the passage illustrates working knowledge of anesthesia in ancient Persia. Later in the 10th century, Abu Bakr Muhammad Bin Zakaria Razi is considered the founder of practical physics and the inventor of the special or net weight of matter. His student, Abu Bakr Joveini, wrote the first comprehensive medical book in the Persian language. After the Islamic conquest of Iran, medicine continued to flourish with the rise of notables such as Rhazes and Haly Abbas, albeit Baghdad was the new cosmopolitan inheritor of Sassanid Jundishapur's medical academy. Rhaze noted that different diseases might have similar signs and symptoms, which highlights Rhazes' contribution to applied neuroanatomy. The differential diagnosis approach is still used in modern medicine. His music therapy was used as a means of promoting healing and he was one of the first people to realize that diet influences the function of the body and the predisposition to disease[20] An idea of the number of medical works composed in Persian alone may be gathered from Adolf Fonahn's Zur Quellenkunde der Persischen Medizin, published in Leipzig in 1910. The author enumerates over 400 works in the Persian language on medicine, excluding authors such as Avicenna, who wrote in Arabic. Author-historians Meyerhof, Casey Wood, and Hirschberg also have recorded the names of at least 80 oculists who contributed treatises on subjects related to ophthalmology from the beginning of 800 AD to the full flowering of Muslim medical literature in 1300 AD. Aside from the aforementioned, two other medical works attracted great attention in medieval Europe, namely Abu Mansur Muwaffaq's Materia Medica, written around 950 AD, and the illustrated Anatomy of Mansur ibn Muhammad, written in 1396 AD. Modern academic medicine began in Iran when Joseph Cochran established a medical college in Urmia in 1878. Cochran is often credited for founding Iran's "first contemporary medical college".[22] The website of Urmia University credits Cochran for "lowering the infant mortality rate in the region"[23] and for founding one of Iran's first modern hospitals (Westminster Hospital) in Urmia. Iran started contributing to modern medical research late in 20th century. Most publications were from pharmacology and pharmacy labs located at a few top universities, most notably Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Ahmad Reza Dehpour and Abbas Shafiee were among the most prolific scientists in that era. Research programs in immunology, parasitology, pathology, medical genetics, and public health were also established in late 20th century. In 21st century, we witnessed a huge surge in the number of publications in medical journals by Iranian scientists on nearly all areas in basic and clinical medicine. Interdisciplinary research were introduced during 2000s and dual degree programs including Medicine/Science, Medicine/Engineering and Medicine/Public health programs were founded. Alireza Mashaghi was one of the main figures behind the development of interdisciplinary research and education in Iran.[citation needed] Astronomy In 1000 AD, Biruni wrote an astronomical encyclopaedia that discussed the possibility that the earth might revolve around the sun. This was before Tycho Brahe drew the first maps of the sky, using stylized animals to depict the constellations. In the tenth century, the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi recorded the first known reference to the Andromeda galaxy, which he called a "little cloud".[24] In 830, the Persian mathematician al-Khwarizmi wrote the first major work of Muslim astronomy. In addition to presenting tables covering the movements of the Sun, Moon and the five planets, Ptolemaic concepts were introduced into Islamic science through this work.[25] BiologyAbu Hanifa Dinawari is considered the founder of Arabic botany for his Kitab al-Nabat (Book of Plants), which consisted of six volumes. Only the third and fifth volumes have survived, though the sixth volume has partly been reconstructed based on citations from later works. In the surviving portions of his works, 637 plants are described from the letters sin to ya. He describes the phases of plant growth and the production of flowers and fruit.[26] Medieval Islamic agronomists including Ibn Bassal and Abū l-Khayr described agricultural and horticultural techniques including how to propagate the olive and the date palm, crop rotation of flax with wheat or barley, and companion planting of grape and olive.[27] ChemistryThe authors of the alchemical texts (c. 850−950) attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan pioneered the chemical use of vegetable and animal substances, which at the time represented an innovative shift towards organic chemistry.[28] One of the innovations in Jabirian alchemy was the addition of sal ammoniac (ammonium chloride) to the category of chemical substances known as 'spirits' (i.e., strongly volatile substances). This included both naturally occurring sal ammoniac and synthetic ammonium chloride as produced from organic substances, and so the addition of sal ammoniac to the list of 'spirits' is likely a product of the new focus on organic chemistry. Since the word for sal ammoniac used in the Jabirian corpus (nūshādhir) is Iranian in origin, it has been suggested that the direct precursors of Jabirian alchemy may have been active in the Hellenizing and Syriacizing schools of the Sasanian Empire.[29] The Persian alchemist and physician Abu Bakr al-Razi (c. 865–925) conducted experiments with the heating of sal ammoniac, vitriol, and other salts, which would eventually lead to the discovery of mineral acids by thirteenth century Latin alchemists such as pseudo-Geber.[30] Physics Kamal al-Din Al-Farisi (1267–1318) born in Tabriz, Iran, is known for giving the first mathematically satisfactory (though incorrect) explanation of the rainbow, and an explication of the nature of colours that reformed the theory of Ibn al-Haytham. Al-Farisi also "proposed a model where the ray of light from the sun was refracted twice by a water droplet, one or more reflections occurring between the two refractions."[31] He tested this through experimentation using a transparent sphere filled with water. Persian PhilosophyAncient Greek, Roman, and medieval European sources refer to the ancient Iranians during the Achaemenid period and earlier (even to Zoroaster himself) as teachers of astronomy, mathematics, philosophy, physics, and other sciences in their time (a similar connection between "knowledge" and "Persia" can be observed in the Christian story of the "Three Wise Men" and also in the famous prophetic hadith that "if knowledge is in the Pleiades, men from Persia will reach it"). Suhrawardi traces the antiquity of wisdom and philosophy, as well as the school of Illumination, back to the Kayanian era (Achaemenids). Henry Corbin believed that Muhammad Husayn Tabatabai and Ashtiyani continued the same divine wisdom that has remained unextinguished in Iran from ancient times to the present. According to Corbin, Iranian thought is the guardian and preserver of a heritage that transcends a limited national perspective, acting as a spiritual universe where guests and pilgrims from other places are welcomed and hosted. Corbin deeply believed that Iranian-Islamic wisdom is imperishable and often spoke of the "imperishable potential of the Iranian spirit".[32][33] Governance Method and ScienceOne of the earliest systematic censuses in world history was conducted during the early Achaemenid period, up until the reign of Darius The Great in Ancient Iran. This census, aimed at financial planning, military organization, bureaucratic needs and tax collection, spanned regions across three continents: Asia, Africa, and Europe. It included data on population numbers, the wealth of cities and provinces (Satrapies), precise assessments of agricultural lands, the resources of each region, and other factors critical to determining state finances and planning for governance and military operations.[34] Science policyThe Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology and the National Research Institute for Science Policy come under the Ministry of Science, Research and Technology. They are in charge of establishing national research policies. The government first set its sights on moving from a resource-based economy to one based on knowledge in its 20-year development plan, Vision 2025, adopted in 2005. This transition became a priority after international sanctions were progressively hardened from 2006 onwards and the oil embargo tightened its grip. In February 2014, the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei introduced what he called the 'economy of resistance', an economic plan advocating innovation and a lesser dependence on imports that reasserted key provisions of Vision 2025.[35] Vision 2025 challenged policy-makers to look beyond extractive industries to the country's human capital for wealth creation. This led to the adoption of incentive measures to raise the number of university students and academics, on the one hand, and to stimulate problem-solving and industrial research, on the other.[35] Iran's successive five-year plans aim to realize collectively the goals of Vision 2025. For instance, in order to ensure that 50% of academic research was oriented towards socio-economic needs and problem-solving, the Fifth Five-Year Economic Development Plan (2010–2015) tied promotion to the orientation of research projects. It also made provision for research and technology centres to be set up on campus and for universities to develop linkages with industry. The Fifth Five-Year Economic Development Plan had two main thrusts relative to science policy. The first was the "islamization of universities', a notion that is open to broad interpretation. According to Article 15 of the Fifth Five-Year Economic Development Plan, university programmes in the humanities were to teach the virtues of critical thinking, theorization and multidisciplinary studies. A number of research centres were also to be developed in the humanities. The plan's second thrust was to make Iran the second-biggest player in science and technology by 2015, behind Turkey. To this end, the government pledged to raise domestic research spending to 3% of GDP by 2015.[35] Yet, R&D's share in the GNP is at 0.06% in 2015 (where it should be at least 2.5% of GDP)[36][37] and industry-driven R&D is almost non‑existent.[38] Vision 2025 fixed a number of targets, including that of raising domestic expenditure on research and development to 4% of GDP by 2025. In 2012, spending stood at 0.33% of GDP.[35] In 2009, the government adopted a National Master Plan for Science and Education to 2025 which reiterates the goals of Vision 2025. It lays particular stress on developing university research and fostering university–industry ties to promote the commercialization of research results.[35][39][40][41][42][43] In early 2018, the Science and Technology Department of the Iranian President's Office released a book to review Iran's achievements in various fields of science and technology during 2017. The book, entitled "Science and Technology in Iran: A Brief Review", provides the readers with an overview of the country's 2017 achievements in 13 different fields of science and technology.[44] Human resourcesIn line with the goals of Vision 2025, policy-makers have made a concerted effort to increase the number of students and academic researchers. To this end, the government raised its commitment to higher education to 1% of GDP in 2006. After peaking at this level, higher education spending stood at 0.86% of GDP in 2015. Higher education spending has resisted better than public expenditure on education overall. The latter peaked at 4.7% of GDP in 2007 before slipping to 2.9% of GDP in 2015. Vision 2025 fixed a target of raising public expenditure on education to 7% of GDP by 2025.[35] Student enrollment trends The result of greater spending on higher education has been a steep rise in tertiary enrollment. Between 2007 and 2013, student rolls swelled from 2.8 million to 4.4 million in the country's public and private universities. Some 45% of students were enrolled in private universities in 2011. There were more women studying than men in 2007, a proportion that has since dropped back slightly to 48%.[35] Enrollment has progressed in most fields. The most popular in 2013 were social sciences (1.9 million students, of which 1.1 million women) and engineering (1.5 million, of which 373 415 women). Women also made up two-thirds of medical students. One in eight bachelor's students go on to enroll in a master's/PhD programme. This is comparable to the ratio in the Republic of Korea and Thailand (one in seven) and Japan (one in ten).[35] The number of PhD graduates has progressed at a similar pace as university enrollment overall. Natural sciences and engineering have proved increasingly popular among both sexes, even if engineering remains a male-dominated field. In 2012, women made up one-third of PhD graduates, being drawn primarily to health (40% of PhD students), natural sciences (39%), agriculture (33%) and humanities and arts (31%). According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 38% of master's and PhD students were studying science and engineering fields in 2011.[35]  There has been an interesting evolution in the gender balance among PhD students. Whereas the share of female PhD graduates in health remained stable at 38–39% between 2007 and 2012, it rose in all three other broad fields. Most spectacular was the leap in female PhD graduates in agricultural sciences from 4% to 33% but there was also a marked progression in science (from 28% to 39%) and engineering (from 8% to 16% of PhD students). Although data are not readily available on the number of PhD graduates choosing to stay on as faculty, the relatively modest level of domestic research spending would suggest that academic research suffers from inadequate funding.[35] The Fifth Five-Year Economic Development Plan (2010–2015) fixed the target of attracting 25 000 foreign students to Iran by 2015. By 2013, there were about 14 000 foreign students attending Iranian universities, most of whom came from Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Syria and Turkey. In a speech delivered at the University of Tehran in October 2014, President Rouhani recommended greater interaction with the outside world. He said that

One in four Iranian PhD students were studying abroad in 2012 (25.7%). The top destinations were Malaysia, the US, Canada, Australia, UK, France, Sweden and Italy. In 2012, one in seven international students in Malaysia was of Iranian origin. There is a lot of scope for the development of twinning between universities for teaching and research, as well as for student exchanges.[35] Trends in researchersAccording to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, the number of (full-time equivalent) researchers rose from 711 to 736 per million inhabitants between 2009 and 2010. This corresponds to an increase of more than 2 000 researchers, from 52 256 to 54 813. The world average is 1 083 per million inhabitants. One in four (26%) Iranian researchers is a woman, which is close to the world average (28%). In 2008, half of researchers were employed in academia (51.5%), one-third in the government sector (33.6%) and just under one in seven in the business sector (15.0%). Within the business sector, 22% of researchers were women in 2013, the same proportion as in Ireland, Israel, Italy and Norway. The number of firms declaring research activities more than doubled between 2006 and 2011, from 30 935 to 64 642. The increasingly tough sanctions oriented the Iranian economy towards the domestic market and, by erecting barriers to foreign imports, encouraged knowledge-based enterprises to localize production.[35] Research expenditureIran's national science budget was about $900 million in 2005 and it had not been subject to any significant increase for the previous 15 years.[45] In 2001, Iran devoted 0.50% of GDP to research and development. Expenditure peaked at 0.67% of GDP in 2008 before receding to 0.33% of GDP in 2012, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics.[46] The world average in 2013 was 1.7% of GDP. Iran's government has devoted much of its budget to research on high technologies such as nanotechnology, biotechnology, stem cell research and information technology (2008).[47] In 2006, the Iranian government wiped out the financial debts of all universities in a bid to relieve their budget constraints.[48] According to the UNESCO science report 2010, most research in Iran is government-funded with the Iranian government providing almost 75% of all research funding.[49] Domestic expenditure on research stood at 0.7% of GDP in 2008 and 0.3% of GDP in 2012. Iranian businesses contributed about 11% of the total in 2008. The government's limited budget is being directed towards supporting small innovative businesses, business incubators and science and technology parks, the type of enterprises which employ university graduates.[35] The share of private businesses in total national R&D funding according to the same report is very low, being just 14%, as compared with Turkey's 48%. The rest of approximately 11% of funding comes from higher education sector and non-profit organizations.[50] A limited number of large enterprises (such as IDRO, NIOC, NIPC, DIO, Iran Aviation Industries Organization, Iranian Space Agency, Iran Electronics Industries or Iran Khodro) have their own in-house R&D capabilities.[51] Funding the transition to a knowledge economy Vision 2025 foresaw an investment of US$3.7 trillion by 2025 to finance the transition to a knowledge economy. It was intended for one-third of this amount to come from abroad but, so far, FDI has remained elusive. It has contributed less than 1% of GDP since 2006 and just 0.5% of GDP in 2014. Within the country's Fifth Five-Year Economic Development Plan (2010–2015), a National Development Fund has been established to finance efforts to diversify the economy. By 2013, the fund was receiving 26% of oil and gas revenue.[35] Much of the US$3.7 trillion earmarked in Vision 2025 is to go towards supporting investment in research and development by knowledge-based firms and the commercialization of research results. A law passed in 2010 provides an appropriate mechanism, the Innovation and Prosperity Fund. According to the fund's president, Behzad Soltani, 4600 billion Iranian rials (circa US$171.4 million) had been allocated to 100 knowledge-based companies by late 2014. Public and private universities wishing to set up private firms may also apply to the fund.[35] Some 37 industries trade shares on the Tehran Stock Exchange. These industries include the petrochemical, automotive, mining, steel, iron, copper, agriculture and telecommunications industries, 'a unique situation in the Middle East'. Most of the companies developing high technologies remain state-owned, including in the automotive and pharmaceutical industries, despite plans to privatize 80% of state-owned companies by 2014. It was estimated in 2014 that the private sector accounted for about 30% of the Iranian pharmaceutical market.[35]  The Industrial Development and Renovation Organization (IDRO) controls about 290 state-owned companies. IDRO has set up special purpose companies in each high-tech sector to coordinate investment and business development. These entities are the Life Science Development Company, Information Technology Development Centre, Iran InfoTech Development Company and the Emad Semiconductor Company. In 2010, IDRO set up a capital fund to finance the intermediary stages of product- and technology-based business development within these companies.[35] Technology parksAs of 2012, Iran had officially 31 science and technology parks nationwide.[citation needed] Furthermore, as of 2014, 36 science and technology parks hosting more than 3,650 companies were operating in Iran.[52] These firms have directly employed more than 24,000 people.[52] According to the Iran Entrepreneurship Association, there are ninety-nine (99) parks of science and technology, in totality, which operate without official permits. Twenty-one of those parks are located in Tehran and affiliated with University Jihad, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran University, Ministry of Energy (Iran), Ministry of Health and Medical Education, and Amir Kabir University among others. Fars province, with 8 parks and Razavi Khorasan province, with 7 parks, are ranked second and third after Tehran respectively.[53]

Innovation As of 2004, Iran's national innovation system (NIS) had not experienced a serious entrance to the technology creation phase and mainly exploited the technologies developed by other countries (e.g. in the petrochemicals industry).[60] In 2016, Iran ranked second in the percentage of graduates in science and engineering in the Global Innovation Index. Iran also ranked fourth in tertiary education, 26 in knowledge creation, 31 in gross percentage of tertiary enrollment, 41 in general infrastructure, 48 in human capital as well as research and 51 in innovation efficiency ratio.[61] In recent years several drugmakers in Iran are gradually developing the ability to innovate, away from generic drugs production itself.[62] According to the State Registration Organization of Deeds and Properties, a total of 9,570 national inventions were registered in Iran during 2008. Compared with the previous year, there was a 38-percent increase in the number of inventions registered by the organization.[63] Iran was ranked 64th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[64] Iran has several funds to support entrepreneurship and innovation:[53]

|