Problem of two emperors

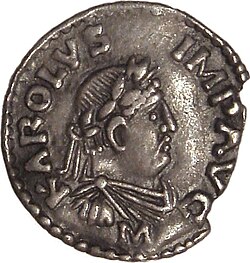

The problem of two emperors or two-emperor problem (deriving from the German term Zweikaiserproblem, Greek: πρόβλημα δύο αυτοκρατόρων)[a] is the historiographical term for the historical contradiction between the idea of the universal empire, that there was only ever one true emperor at any one given time, and the truth that there were often multiple individuals who claimed the position simultaneously. The term is primarily used in regards to medieval European history and often refers to in particular the long-lasting dispute between the Byzantine emperors in Constantinople and the Holy Roman emperors in modern-day Germany and Austria as to which monarch represented the legitimate Roman emperor. In the view of medieval Christians, the Roman Empire was indivisible and its emperor held a somewhat hegemonic position even over Christians who did not live within the formal borders of the empire. Since the collapse of the Western Roman Empire during late antiquity, the Byzantine Empire (which represented its surviving provinces in the East) had been recognized as the legitimate Roman Empire by itself, the pope, and the various new Christian kingdoms throughout Europe. This changed in 797 when Emperor Constantine VI was deposed, blinded, and replaced as ruler by his mother, Empress Irene, whose rule was ultimately not accepted in Western Europe, the most frequently cited reason being that she was a woman. Rather than recognizing Irene, Pope Leo III proclaimed the king of the Franks, Charlemagne, as the emperor of the Romans in 800 under the concept of translatio imperii (transfer of imperial power). Although the two empires eventually relented and recognized each other's rulers as emperors, they never explicitly recognized the other as "Roman", with the Byzantines referring to the Holy Roman emperor as the 'emperor (or king) of the Franks' and later as the 'king of Germany' and the western sources often describing the Byzantine emperor as the 'emperor of the Greeks' or the 'emperor of Constantinople'. Over the course of the centuries after Charlemagne's coronation, the dispute in regards to the imperial title was one of the most contested issues in Holy Roman–Byzantine politics. Though military action rarely resulted because of it, the dispute significantly soured diplomacy between the two empires. This lack of war was probably mostly on account of the geographical distance between the two empires. On occasion, the imperial title was claimed by neighbors of the Byzantine Empire, such as Bulgaria and Serbia, which often led to military confrontations. As the Byzantine emperors had large control over the Patriarchate of Constantinople (Caesaropapism), their rivals often declared their own patriarchates independent from it. After the Byzantine Empire was momentarily overthrown by the Catholic crusaders of the Fourth Crusade in 1204 and supplanted by the Latin Empire, the dispute continued even though both emperors now followed the same religious head for the first time since the dispute began. Though the Latin emperors recognized the Holy Roman emperors as the legitimate Roman emperors, they also claimed the title for themselves, which was not recognized by the Holy Roman Empire in return. Pope Innocent III eventually accepted the idea of divisio imperii (division of empire), in which imperial hegemony would be divided into West (the Holy Roman Empire) and East (the Latin Empire). Some regions remained outside the Frankokratia, where new Byzantine pretenders resided. Although the Latin Empire was destroyed by the resurgent Byzantine Empire under the Palaiologos dynasty in 1261, the Palaiologoi never reached the power of the pre-1204 Byzantine Empire and its emperors ignored the problem of two emperors in favor of closer diplomatic ties with the west due to a need for aid against the many enemies of their empire and to end their support for the Latin pretenders. The problem of two emperors only fully resurfaced after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, after which the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II claimed the imperial dignity as Kayser-i Rûm (Caesar of the Roman Empire) and aspired to claim universal hegemony. The Ottoman sultans were recognized as emperors by the Holy Roman Empire in the 1533 Treaty of Constantinople, but the Holy Roman emperors were not recognized as emperors in turn. The Ottoman sultans slowly abandoned Roman legitimization when the empire started to transform and started to prefer the Persian padishah title but still held up to universal hegemony. The Ottomans called the Holy Roman emperors by the title kıral (king) for one and a half centuries, until the Sultan Ahmed I formally recognized Rudolf II as an emperor in the Peace of Zsitvatorok in 1606, an acceptance of divisio imperii, bringing an end to the dispute between Constantinople and Western Europe. In addition to the Ottomans, the Tsardom of Russia and the later Russian Empire also claimed the Roman legacy of the Byzantine Empire, with its rulers titling themselves as tsar (deriving from "caesar") and later imperator. By then Ottomans saw themselves as their overlords rather than Roman emperors. The tsar title was recognized by other states at times but not universally translated as "emperor" pushing the Russians to adopt more similar titles to their rivals. Their claim to the imperial title and equal status was not recognized by the Holy Roman Empire until 1745 and by the Ottoman Empire until 1774. While the Holy Roman Empire dissolved in 1806, the Russian rulers continued to claim the succession of the Byzantine Empire until 1917. The Greek Plan of the 1780s was the last serious attempt of restoring the Christian Byzantine Empire as a third empire alongside Russia and the Holy Roman Empire. By the 19th century, the title "emperor" and their variations became detached from Roman Empire with the title being regularly used by different states established under the rule of European royal dynasties including Austria (1804–1918; 1804–06 even alongside the Holy Roman emperor title), Brazil (1822–1889), Ethiopia (1936–1941), France (1804–14, 1815, 1852–70), Germany (1871–1918), India (1876–1948) and Mexico (1863–1867) with little to no reference to the Roman Empire and did not claim universal hegemony.[1] Non-European states like in East Asia also started being referred to as "empires". The latest tsars of Bulgaria (1908–1946) and the basileis of Greece (1832–1973) were seen as kings rather than emperors. BackgroundPolitical background Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, Roman civilization endured in the remaining eastern half of the Roman Empire, often termed by historians as the Byzantine Empire (though it self-identified simply as the "Roman Empire"). As the Roman emperors had done in antiquity, the Byzantine emperors saw themselves as universal rulers. The idea was that the world contained one empire (the Roman Empire) and one church and this idea survived despite the collapse of the empire's western provinces. Although the last extensive attempt at putting the theory back into practice had been Justinian I's wars of reconquest in the 6th century, which saw the return of Italy and Africa into imperial control, the idea of a great western reconquest remained a dream for Byzantine emperors for centuries.[2] Because the empire was constantly threatened at critical frontiers to its north and east, the Byzantines were unable to focus much attention to the west and Roman control would slowly disappear in the west once more. Nevertheless, their claim to the universal empire was acknowledged by temporal and religious authorities in the west, even if this empire couldn't be physically restored. Gothic and Frankish kings in the fifth and sixth centuries acknowledged the emperor's suzerainty, as a symbolic acknowledgement of membership in the Roman Empire also enhanced their own status and granted them a position in the perceived world order of the time. As such, Byzantine emperors could still perceive the west as the western part of their empire, momentarily in barbarian hands, but still formally under their control through a system of recognition and honors bestowed on the western kings by the emperor.[2] A decisive geopolitical turning point in the relations between East and West was during the long reign of emperor Constantine V (741–775). Though Constantine V conducted several successful military campaigns against the enemies of his empire, his efforts were centered on the Muslims and the Bulgars, who represented immediate threats. Because of this, the defense of Italy was neglected. The main Byzantine administrative unit in Italy, the Exarchate of Ravenna, fell to the Lombards in 751, ending the Byzantine presence in northern Italy.[3] The collapse of the Exarchate had long-standing consequences. The popes, ostensibly Byzantine vassals, realized that Byzantine support was no longer a guarantee and increasingly began relying on the major kingdom in the West, the Frankish Kingdom, for support against the Lombards. Byzantine possessions throughout Italy, such as Venice and Naples, began to raise their own militias and effectively became independent. Imperial authority ceased to be exercised in Corsica and Sardinia and religious authority in southern Italy was formally transferred by the emperors from the popes to the patriarchs of Constantinople. The Mediterranean world, interconnected since the days of Roman Empire of old, had been definitively divided into East and West.[4]  In 797, the young emperor Constantine VI was arrested, deposed and blinded by his mother and former regent, Irene of Athens. She then governed the empire as its sole ruler, taking the title Basileus rather than the feminine form Basilissa (used for the empresses who were wives of reigning emperors). At the same time, the political situation in the West was rapidly changing. The Frankish Kingdom had been reorganized and revitalized under King Charlemagne.[5] Though Irene had been on good terms with the papacy prior to her usurpation of the Byzantine throne, the act soured her relations with Pope Leo III. At the same time, Charlemagne's courtier Alcuin had suggested that the imperial throne was now vacant since a woman claimed to be emperor, perceived as a symptom of the decadence of the empire in the east.[6] Possibly inspired by these ideas and possibly viewing the idea of a woman emperor as an abomination, Pope Leo III also began to see the imperial throne as vacant. When Charlemagne visited Rome for Christmas in 800 he was treated not as one territorial ruler among others, but as the sole legitimate monarch in Europe and on Christmas Day he was proclaimed and crowned by Pope Leo III as the Emperor of the Romans.[5] Rome and the idea of the Universal Empire Though the Roman Empire is an example of a universal monarchy, the idea is not exclusive to the Romans, having been expressed in unrelated entities such as the Aztec Empire and in earlier realms such as the Persian and Assyrian Empires.[7] Most "universal monarchs" justified their ideology and actions through the divine; proclaiming themselves (or being proclaimed by others) as either divine themselves or as appointed on the behalf of the divine, meaning that their rule was theoretically sanctioned by heaven. By tying together religion with the empire and its ruler, obedience to the empire became the same thing as obedience to the divine. Like its predecessors, the Ancient Roman religion functioned in much the same way, conquered peoples were expected to participate in the imperial cult regardless of their faith before Roman conquest. This imperial cult was threatened by religions such as Christianity (where Jesus Christ is explicitly proclaimed as the "Lord"), which is one of the primary reasons for the harsh persecutions of Christians during the early centuries of the Roman Empire; the religion was a direct threat to the ideology of the regime. Although Christianity eventually became the state religion of the Roman Empire in the 4th century, the imperial ideology was far from unrecognizable after its adoption. Like the previous imperial cult, Christianity now held the empire together and though the emperors were no longer recognized as gods, the emperors had successfully established themselves as the rulers of the Christian church in the place of Christ, still uniting temporal and spiritual authority.[7] In the Byzantine Empire, the authority of the emperor as both the rightful temporal ruler of the Roman Empire and the head of Christianity remained unquestioned until the fall of the empire in the 15th century.[8] The Byzantines firmly believed that their emperor was God's appointed ruler and his viceroy on Earth (illustrated in their title as Deo coronatus, "crowned by God"), that he was the Roman emperor (basileus ton Rhomaion), and as such the highest authority in the world due to his universal and exclusive emperorship. The emperor was an absolute ruler dependent on no one when exercising his power (illustrated in their title as autokrator, or the Latin moderator).[9] The Emperor was adorned with an aura of holiness and was theoretically not accountable to anyone but God himself. The Emperor's power, as God's viceroy on Earth, was also theoretically unlimited. In essence, Byzantine imperial ideology was simply a Christianization of the old Roman imperial ideology, which had also been universal and absolutist.[10] As the Western Roman Empire collapsed and subsequent Byzantine attempts to retain the west crumbled, the church took the place of the empire in the west and by the time Western Europe emerged from the chaos endured during the 5th to 7th centuries, the pope was the chief religious authority and the Franks were the chief temporal authority. Charlemagne's coronation as Roman emperor expressed an idea different from the absolutist ideas of the emperors in the Byzantine Empire. Though the eastern emperor retained control of both the temporal empire and the spiritual church, the rise of a new empire in the west was a collaborative effort, Charlemagne's temporal power had been won through his wars, but he had received the imperial crown from the pope. Both the emperor and the pope had claims to ultimate authority in Western Europe (the popes as the successors of Saint Peter and the emperors as divinely appointed protectors of the church) and though they recognized the authority of each other, their "dual rule" would give rise to many controversies (such as the Investiture Controversy and the rise and fall of several antipopes).[8] Holy Roman–Byzantine disputeCarolingian periodImperial ideology Though the inhabitants of the Byzantine Empire itself never stopped referring to themselves as "Romans" (Rhomaioi), sources from Western Europe from the coronation of Charlemagne and onwards denied the Roman legacy of the eastern empire by referring to its inhabitants as "Greeks". The idea behind this renaming was that Charlemagne's coronation did not represent a division (divisio imperii) of the Roman Empire into West and East nor a restoration (renovatio imperii) of the old Western Roman Empire. Rather, Charlemagne's coronation was the transfer (translatio imperii) of the imperium Romanum from the Greeks in the east to the Franks in the west.[11] To contemporary sources in Western Europe, such as the Annals of Lorsch, Charlemagne's key legitimizing factor as emperor (other than papal approval) was the territories which he controlled. As he controlled formerly Roman lands in Gaul, Germany and Italy (including Rome itself), and acted as a true emperor in these lands, he deserved to be called emperor, while the eastern emperor was seen as having abandoned these traditional provinces.[12][13] This argument from antiquity or tradition had more longevity than Alcuin of York's argument that the Roman emperor could not be a woman and therefore was automatically vacant upon Irene of Athens' usurpation in 797, since Irene herself was deposed in 802 and followed by male rulers for the rest of Charlemagne's reign.[13] Although crowned as an explicit refusal of the eastern emperor's claim to universal rule, Charlemagne himself does not appear to have been interested in open confrontation with the Byzantine Empire or its rulers, and seems to have desired to eliminate the appearance of division diplomatically.[12] When Charlemagne wrote to Constantinople in 813, Charlemagne titled himself as the "Emperor and Augustus and also King of the Franks and of the Lombards", identifying the imperial title with his previous royal titles in regards to the Franks and Lombards, rather than to the Romans. As such, his imperial title could be interpreted by the Byzantines as stemming from the fact that he was the king of more than one kingdom (equating the title of emperor with that of king of kings), rather than signifying a usurpation of Byzantine power.[12] Nevertheless, Charlemagne's coronation was in actuality an active challenge to Byzantine imperial legitimacy and was regarded as such by the Pope.[14] On his coins, the name and title used by Charlemagne is Karolus Imperator Augustus and in his own documents he used Imperator Augustus Romanum gubernans Imperium ("august emperor, governing the Roman Empire") and serenissimus Augustus a Deo coronatus, magnus pacificus Imperator Romanorum gubernans Imperium ("most serene Augustus crowned by God, great peaceful emperor governing the empire of the Romans").[15] The identification as an "emperor governing the Roman Empire" rather than a "Roman emperor" could be seen as an attempt at avoiding the dispute and issue over who was the true emperor and attempting to keep the perceived unity of the empire intact.[12]  In response to the Frankish adoption of the imperial title, the Byzantine emperors (which had previously simply used "emperor" as a title) adopted the full title of "emperor of the Romans" to make their supremacy clear.[15] To the Byzantines, Charlemagne's coronation was a rejection of their perceived order of the world and an act of usurpation. Although Emperor Michael I (r. 811–813) eventually relented and recognized Charlemagne as an emperor and a "spiritual brother" of the eastern emperor, Charlemagne was not recognized as the Roman emperor and his imperium was seen as limited to his actual domains (as such not universal) and not as something that would outlive him (with his successors being referred to as "kings" rather than emperors in Byzantine sources).[16] Following Charlemagne's coronation, the two empires engaged in diplomacy with each other. The exact terms discussed are unknown and negotiations were slow but it seems that Charlemagne proposed in 802 that he and Irene would marry and unite their empires, sending ambassadors to Constantinople.[17] As such, the empire could have "reunited" without arguments as to which ruler was the legitimate one.[12] However, as reported by Theophanes the Confessor, the scheme was frustrated by Aetios, eunuch and favorite of Irene, who was attempting to usurp her on behalf of his brother Leo, even though Irene herself approved of the marriage proposal. The General Logothete (finance minister) Nikephoros, along with other courtiers disgruntled with Irene's financial policy and fearful of the implications of political union with the Franks through the proposed marriage, overthrew Irene and exiled her on 31 October 802 while the Frankish and papal ambassadors were still in the city, damaging Frankish-Byzantine relations once again.[18] Louis II and Basil I One of the primary resources in regards to the problem of two emperors in the Carolingian period is a letter by Emperor Louis II. Louis II was the fourth emperor of the Carolingian Empire, though his domain was confined to northern Italy as the rest of the empire had fractured into several different kingdoms, though these still acknowledged Louis as the emperor. His letter was a reply to a provocative letter by Byzantine emperor Basil I. Though Basil's letter is lost, its contents can be ascertained from the known geopolitical situation at the time and Louis's reply and probably related to the ongoing co-operation between the two empires against the Muslims. The focal point of Basil's letter was his refusal to recognize Louis II as a Roman emperor.[19] Basil appears to have based his refusal on two main points. First of all, the title of Roman emperor was not hereditary (the Byzantines still considered it to formally be a republican office, although also tied intimately with religion) and second of all, it was not considered appropriate for someone of a gens (e.g. an ethnicity) to hold the title. The Franks, and other groups throughout Europe, were seen as different gentes but to Basil and the rest of the Byzantines, "Roman" was not a gens. Romans were defined chiefly by their lack of a gens and as such, Louis was not Roman and thus not a Roman emperor. There was only one Roman emperor, Basil himself, and though Basil considered that Louis could be an emperor of the Franks, he appears to have questioned this as well seeing as only the ruler of the Romans was to be titled basileus (emperor).[19] As illustrated by Louis's letter, the western idea of ethnicity was different from the Byzantine idea; everyone belonged to some form of ethnicity. Louis considered the gens romana (Roman people) to be the people who lived in the city of Rome, which he saw as having been deserted by the Byzantine Empire. All gentes could be ruled by a basileus in Louis's mind and as he pointed out, the title (which had originally simply meant "king") had been applied to other rulers in the past (notably Persian rulers). Furthermore, Louis disagreed with the notion that someone of a gens could not become the Roman emperor. He considered the gentes of Hispania (the Theodosian dynasty), Isauria (the Isaurian dynasty), and Khazaria (Leo IV) as all having provided emperors, though the Byzantines themselves would have seen all of these as Romans and not as peoples of gentes. The views expressed by the two emperors in regards to ethnicity are somewhat paradoxical; Basil defined the Roman Empire in ethnic terms (defining it as explicitly against ethnicity) despite not considering the Romans as an ethnicity and Louis did not define the Roman Empire in ethnic terms (defining it as an empire of God, the creator of all ethnicities) despite considering the Romans as an ethnic people.[19]  Louis also derived legitimacy from religion. He argued that as the Pope of Rome, who actually controlled the city, had rejected the religious leanings of the Byzantines as heretical, instead favoring the Franks, and also because the he had also crowned him emperor, Louis was the legitimate Roman emperor. The idea was that it was God himself, acting through his vicar the Pope, who had granted the church, people and city of Rome to him to govern and protect.[19] Louis's letter details that if he was not the emperor of the Romans then he could not be the emperor of the Franks either, as it was the Roman people themselves who had accorded his ancestors with the imperial title. In contrast to the papal affirmation of his imperial lineage, Louis chastized the eastern empire for its emperors mostly only being affirmed by their senate and sometimes lacking even that, with some emperors having been proclaimed by the army, or worse, women (probably a reference to Irene). Louis probably overlooked that affirmation by the army was the original ancient source for the title of imperator, before it came to mean the ruler of the Roman Empire.[20] Though it would have been possible for either side of the dispute to concede to the obvious truth, that there were now two empires and two emperors, this would have denied the understood nature of what the empire was and meant (its unity).[12] Louis's letter does offer some evidence that he might have recognized the political situation as such; Louis is referred to as the "august emperor of the Romans" and Basil is referred to as the "very glorious and pious emperor of New Rome",[21] and he suggests that the "indivisible empire" is the empire of God and that "God has not granted this church to be steered either by me or you alone, but so that we should be bound to each other with such love that we cannot be divided, but should seem to exist as one".[19] These references are more likely to mean that Louis still considered there to be a single empire, but with two imperial claimants (in effect an emperor and an anti-emperor). Neither side in the dispute would have been willing to reject the idea of the single empire. Louis referring to the Byzantine emperor as an emperor in the letter may simply be a courtesy, rather than an implication that he truly accepted his imperial rule.[22] Louis's letter mentions that the Byzantines abandoned Rome, the seat of empire, and lost the Roman way of life and the Latin language. In his view, that the empire was ruled from Constantinople did not represent it surviving, but rather that it had fled from its responsibilities.[21] Although he would have had to approve its contents, Louis probably did not write his letter himself and it was probably instead written by the prominent cleric Anastasius Bibliothecarius. Anastasius was not a Frank but a citizen of the city of Rome (in Louis's view an "ethnic Roman"). As such, prominent figures in Rome itself would have shared Louis's views, illustrating that by his time, the Byzantine Empire and the city of Rome had drifted very far apart.[19] Following the death of Louis in 875, emperors continued to be crowned in the West for a few decades, but their reigns were often brief and problematic and they only held limited power and as such the problem of two emperors ceased being a major issue to the Byzantines, for a time.[23] Ottonian period The problem of two emperors returned when Pope John XII crowned the king of Germany, Otto I, as emperor of the Romans in 962, almost 40 years after the death of the previous papally crowned emperor, Berengar. Otto's repeated territorial claims to all of Italy and Sicily (as he had also been proclaimed as the king of Italy) brought him into conflict with the Byzantine Empire.[24] The Byzantine emperor at the time, Romanos II, appears to have more or less ignored Otto's imperial aspirations, but the succeeding Byzantine emperor, Nikephoros II, was strongly opposed to them. Otto, who hoped to secure imperial recognition and the provinces in southern Italy diplomatically through a marriage alliance, dispatched diplomatic envoys to Nikephoros in 967.[23] To the Byzantines, Otto's coronation was a blow as, or even more, serious than Charlemagne's as Otto and his successors insisted on the Roman aspect of their imperium more strongly than their Carolingian predecessors.[25] Leading Otto's diplomatic mission was Liutprand of Cremona, who chastized the Byzantines for their perceived weakness; losing control of the West and thus also causing the pope to lose control of the lands which belonged to him. To Liutprand, the fact that Otto I had acted as a restorer and protector of the church by restoring the lands of the papacy (which Liutprand believed had been granted to the pope by Emperor Constantine I), made him the true emperor while the loss of these lands under preceding Byzantine rule illustrated that the Byzantines were weak and unfit to be emperors.[22] Liutprand expresses his ideas with the following words in his report on the mission, in a reply to Byzantine officials:[26]

Nikephoros pointed out to Liutprand personally that Otto was a mere barbarian king who had no right to call himself an emperor, nor to call himself a Roman.[27] Just before Liutprand's arrival in Constantinople, Nikephoros II had received an offensive letter from Pope John XIII, possibly written under pressure from Otto, in which the Byzantine emperor was referred to as the "Emperor of the Greeks" and not the "Emperor of the Romans", denying his true imperial status. Liutprand recorded the outburst of Nikephoros's representatives at this letter, which illustrates that the Byzantines too had developed an idea similar to translatio imperii regarding the transfer of power from Rome to Constantinople:[22]

Liutprand attempted to diplomatically excuse the pope by stating that the pope had believed that the Byzantines would not like the term "Romans" since they had moved to Constantinople and changed their customs and assured Nikephoros that in the future, the eastern emperors would be addressed in papal letters as "the great and august emperor of the Romans".[28] Otto's attempted cordial relations with the Byzantine Empire would be hindered by the problem of the two emperors, and the eastern emperors were less than eager to reciprocate his feelings.[26] Liutprand's mission to Constantinople was a diplomatic disaster, and his visit saw Nikephoros repeatedly threaten to invade Italy, restore Rome to Byzantine control and on one occasion even threaten to invade Germany itself, stating (concerning Otto) that "we will arouse all the nations against him; and we will break him in pieces like a potter's vessel".[26] Otto's attempt at a marriage alliance would not materialize until after Nikephoros's death. In 972, in the reign of Byzantine emperor John I Tzimiskes, a marriage was secured between Otto's son and co-emperor Otto II and John's niece Theophanu.[24] Though Emperor Otto I briefly used the title imperator augustus Romanorum ac Francorum ("august emperor of Romans and Franks") in 966, the style he used most commonly was simply Imperator Augustus. Otto leaving out any mention of Romans in his imperial title may be because he wanted to achieve the recognition of the Byzantine emperor. Following Otto's reign, mentions of the Romans in the imperial title became more common. In the 11th century, the German king (the title held by those who were later crowned emperors) was referred to as the rex Romanorum ("king of the Romans") and in the century after that, the standard imperial title was dei gratia Romanorum Imperator semper Augustus ("by the Grace of God, emperor of the Romans, ever august").[15] Hohenstaufen periodTo Liutprand of Cremona and later scholars in the west, the eastern emperors were perceived as weak, degenerate, and not true emperors; there was, they felt, a single empire under the true emperors (Otto I and his successors), who demonstrated their right to the empire through their restoration of the Church. In return, the eastern emperors did not recognize the imperial status of their challengers in the west. Although Michael I had referred to Charlemagne by the title Basileus in 812, he hadn't referred to him as the Roman emperor. Basileus in of itself was far from an equal title to that of Roman emperor. In their own documents, the only emperor recognized by the Byzantines was their own ruler, the Emperor of the Romans. In Anna Komnene's The Alexiad (c. 1148), the Emperor of the Romans is her father, Alexios I, while the Holy Roman emperor Henry IV is titled simply as the "King of Germany".[28] According to Arnold of Lübeck, when King of Romans Conrad III met Byzantine emperor Manuel I Komnenos in 1147 (who he calls "King of the Greeks"),[b] Conrad III refused to submit to Manuel I so they rode to each other and gave each other a welcoming kiss. The accuracy of the account remains disputed.[29] In the 1150s, the Byzantine emperor Manuel I Komnenos became involved in a three-way struggle between himself, the Holy Roman emperor Frederick I Barbarossa and the Italo-Norman King of Sicily, Roger II. Manuel aspired to lessen the influence of his two rivals and at the same time win the recognition of the Pope (and thus by extension Western Europe) as the sole legitimate emperor, which would unite Christendom under his sway. Manuel reached for this ambitious goal by financing a league of Lombard towns to rebel against Frederick and encouraging dissident Norman barons to do the same against the Sicilian king. Manuel even dispatched his army to southern Italy, the last time a Byzantine army ever set foot in Western Europe. Despite his efforts, Manuel's campaign ended in failure and he won little except the hatred of both Barbarossa and Roger, who by the time the campaign concluded had allied with each other.[30] Frederick Barbarossa's crusadeThe choice of the Holy Roman emperor Frederick I Barbarossa (left) to march through the Byzantine Empire during the Third Crusade in 1189 caused the Byzantine emperor, Isaac II Angelos (right), to panic and nearly caused a full-scale war between the Byzantine Empire and Western Christianity. Soon after the conclusion of the Byzantine–Norman wars in 1185, the Byzantine emperor Isaac II Angelos received word that a Third Crusade had been called due to Sultan Saladin's 1187 conquest of Jerusalem. Isaac learnt that Barbarossa, a known foe of his empire, was to lead a large contingent in the footprints of the First and Second crusades through the Byzantine Empire. Isaac II interpreted Barbarossa's march through his empire as a threat and considered it inconceivable that Barbarossa did not also intend to overthrow the Byzantine Empire.[31] As a result of his fears, Isaac II imprisoned numerous Latin citizens in Constantinople.[32] In his treaties and negotiations with Barbarossa (which exist preserved as written documents), Isaac II was insincere as he had secretly allied with Saladin to gain concessions in the Holy Land and had agreed to delay and destroy the German army.[32] Barbarossa, who did not in fact |