Multifocal stenosing ulceration of the small intestine

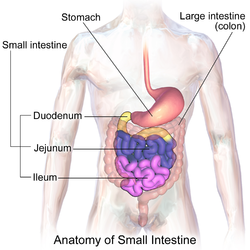

Multifocal stenosing ulceration of the small intestine is a rare condition that is characterised by recurrent ulcers of the small intestine.[citation needed] Signs and symptomsThe clinical features of this condition are variable. Features associated with it include:[citation needed] Faecal occult blood testing is usually positive. Laboratory investigations normally show anaemia and low albumin. CauseA mutation in the cytosolic phospholipase A2-α gene (PLA2G4A) has been identified as the cause of this disease in one family.[1] In this family the mutation was inherited as an autosomal recessive. It is not yet known if this gene is the cause of this disease in other families. The gene encoding cytosolic phospholipase A2-α is found on chromosome 1. Cytosolic phospholipase A2-α acts on membrane phospholipids to release arachidonic acid a precursor in the synthesis of eicosanoids. The eicosanoids are involved in multiple regulatory pathways. PathologyThis disease is characterised by multifocal stenosing ulceration of the small intestine. The ulcers are circular or irregular in shape and their margins are always clear. The lesions involve only the mucosa and submucosa and are confined to the jejunum and proximal ileum. The intervening mucosa appears normal. Nonspecific inflammatory changes are present. Giant cells or other typical features of granulomatous inflammation are not found. Multiple stenoses are typically present (mean 8: range 1–25). DiagnosisThis may be difficult given the non specific nature of the presenting symptoms and the rarity of the condition itself. It is normally made by the combination of the clinical picture, endoscopic findings and typical histology. Radiology may also be helpful. Other conditions such as infections and vasculitis should be ruled out with the relevant laboratory investigations. Differential diagnosis

TreatmentSteroids seem to relieve the symptoms but long term treatment may be required.[2] Other immunosuppressants appear to be less effective. Surgery may be curative in ~40% but a second operation may be required later.[citation needed] PrognosisThis condition may be lifelong. Although not normally fatal, it may necessitate admission to hospital for transfusions, control of bleeding or other complications. Because of its rarity, to date there have been no controlled trials. Treatment remains empirical and symptomatic. HistoryThis disease was first recognised in 1959.[3] It was redescribed and named 'cryptogenetic plurifocal ulcerative stenosing enteritis' in 1964.[4] References

|

||||