History of Mainz The city of Mainz has Roman origins and can look back on over 2,000 years of history. Founded as the Roman legion camp Mogontiacum, the city later became the capital of the province of Germania superior and was the seat of the archbishop from 780/82 to 1803. The city experienced its heyday between 1244 and 1462, when it was a free city. After that, its history was shaped by the Electors and Archbishops of Mainz, who resided in the city, until the end of the 18th century. After this era, Mainz largely lost its importance as a federal fortress, while its role as a fortress increased. In 1946, Mainz became the capital of Rhineland-Palatinate.[1] BackgroundHuman life in the area around present-day Mainz has been documented as far back as 20,000 to 25,000 years ago. In 1921, a hunting camp dating back to the last Ice Age was uncovered on Mainz's Linsenberg hill. This important relic has been recorded in specialist literature and is the oldest trace of human life in the Mainz area.[1]  Due to the Rhine River, which has been the city's lifeline since its inception, a rich cultural and ethnic life flourished in the area now known as Mainz after the end of the Stone Age, particularly around 1800 BC, continuing through the Bronze Age and all subsequent eras. In the second half of the 1st millennium BC, the Celts were the dominant power in the Upper Rhine region. They also settled in the Mainz area and named this settlement, which was not comparable to a city, after one of their gods, Mogon. The Romans who arrived later derived the city name Mogontiacum from this name, which was first mentioned by Tacitus.[1]  In 75 BC, the Germanic tribes under the leadership of Ariovistus arrived near Mainz, where they crossed the Rhine toward Gaul. The Celts who had been living on the Middle Rhine until then were pushed back, although in the Mainz area, which belonged to the outer sphere of influence of the Celtic Treveri tribe, the proportion of the Celtic population remained relatively intact until the arrival of the Romans.[1] After the Gallic Wars, which ended with the Battle of Alesia in 52 BC, the Roman Empire under Julius Caesar and later Augustus turned its attention to the Rhine and Germania. The Romans first conquered the areas on the left bank of the Rhine to subjugate Germania Magna on the right bank. One of the camps built on the Rhine as part of this plan was Mogontiacum, founded in 13/12 BC by Nero Claudius Drusus. The city is therefore one of the oldest in Germany.[1] Roman period Mogontiacum belonged to the Roman Empire for nearly 500 years. An earlier date given for the founding of the legionary camp in 38 BC cannot be verified archaeologically and is no longer tenable today. Nevertheless, it was officially used as the occasion for the two-thousandth anniversary celebrations in 1962. The reliably dated beginning of Roman history in Mainz is set at 13/12 BC. As part of the Roman Empire's expansion policy toward Germania, a legionary camp was established at the mouth of the Main near Mainz at this time, and Roman rule was permanently established as far as the Rhine. Nero Claudius Drusus was responsible for this until his death in 9 BC.[2]   Until 90 AD, only two legions were permanently stationed in the camp (starting with the 14th Legion Gemina and the 16th Legion Gallica), later one legion (22nd Legion Primigenia Pia Fidelis, the Mainz "house legion" until the middle of the 4th century AD). In preparation for various campaigns in Germania, up to four legions and auxiliary troops were temporarily stationed in Mainz. Some of these additional troops were housed in a second large military camp, which existed until the end of the 1st century AD. It was located near Weisenau on the site of today's quarry and can no longer be traced archaeologically. As a result, the military base Mogontiacum also attracted traders, craftsmen, and innkeepers. However, the people living around the camp had no civil rights and were dependent on the commandant of the camp. The main camp, which is still remembered in the name of the present-day district Kästrich (Castrum), was structured like other Roman camps: two intersecting roads (Via praetoria, Via principalis, Via decumana) with four gates (Porta praetoria, Porta decumana, Porta principalis dextra, Porta principalis sinistra).[2]  After the disaster in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD, the Rhine became the border river between Germania and the Empire. In 89 AD, after the suppression of the Saturninus uprising, the city became not only the most important military camp on the Rhine border but also the civil administrative centre and capital of the newly formed province of Germania superior (Upper Germania). The province stretched from the Upper Rhine to Koblenz, then called Confluentes. To the north lay the province of Germania Inferior with Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium (Cologne) as its provincial capital. A comprehensive building program, especially by the Flavian imperial family (expansion of the legionary camp in stone, aqueduct construction, permanent pile bridge with massive stone piers), as well as the conquest of the Wetterau and the beginning of the construction of the Limes there, characterized the development of Mogontiacum in the 1st century AD.[2] Mainz subsequently flourished, but as a civilian settlement, it never achieved the status of Cologne or Trier. Trade routes, for example, to Divodurum (Metz), made the city prosperous. However, from the end of the 2nd century AD, the city and its surroundings were increasingly threatened by invading tribes such as the Chatti, Alamanni, and Vandals, especially after the fall of the Limes in 258 AD.[2] This led to the loss of the Limes territory on the right bank of the Rhine in 259/260 AD, and Mogontiacum once again became a border town. Christianity also arrived in the city in the third or fourth century at the latest. By 368, there is evidence of a bishop in the city (see also: History of the Diocese of Mainz).[2] However, during the same century, the decline of the Roman Empire became increasingly apparent. The Alamanni, in particular, threatened Mainz and occupied the city in 352/355. Further invasions are documented in 357, 368, and 370. Julian recaptured the city from the Alamanni in 357 AD and reinforced the Rhine fleet in Mainz (Roman ships). The city wall, which had been built in the 3rd century AD, was also rebuilt and renovated in the second half of the 4th century. On New Year's Eve 407, the Vandals conquered the city and destroyed it (see: Crossing of the Rhine in 406). In 451, the Huns invaded, but according to the latest research, they did not cause much damage in Mainz. However, this marked the end of Roman Mainz. The Franks took over and incorporated Mainz into their empire at the end of the 5th century.[2] Merovingians, Carolingians, and Ottonians Toward the end of the 5th century, a battle broke out between the Franks and the Alamanni, the second-largest tribe in the region, for supremacy over the former Roman territories. In 496/97, the Frankish king Clovis I of the Merovingian dynasty was baptised after taking a vow. Clovis subsequently drove the Alamanni out of the region. He became king of West Francia and Gaul, and later also of the Frankish Empire in Cologne, which presumably included Mainz. Mainz thus became part of a large Frankish empire and developed from a border town into an inner city. From this time onward, but especially during the time of Bishop Sidonius (6th century), Christianity flourished in the city, and construction work began again for the first time. The 7th and 8th centuries saw the beginning of missionary work by Benedictine monks from the Anglo-Saxon region. The most important of these missionaries was Boniface, the missionary archbishop from Wessex. In 744, he deposed Gewilius, who was deemed unworthy due to his practice of blood feuds, and became bishop of Mainz himself, from where he initiated the Christianization of Hesse and Friesland. Under his successor, Lullus (Lul), the bishopric was elevated to an archbishopric around 780/782. The Church of Mainz developed into the largest ecclesiastical province north of the Alps (see: Diocese of Mainz), which also emphasised the importance of the city itself.[3] The great era of the Carolingians began with Charlemagne. Charlemagne founded one of his imperial palaces near Mainz in Ingelheim. The discovery of a fragment of a Carolingian throne from the second half of the 8th century suggests that there was also an imperial palace in Mainz. Charlemagne held several assemblies in Mainz, a tradition that continued for centuries and reached its peak in 1184 under Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa. Mainz was an ideal venue for conferences as it had a large church (75 meters long) in the St. Alban monastery near Mainz, which could be used for meetings and thus became the spiritual centre of the diocese over the next 200 years. Since Mainz had been actively promoting the Christianization of the Slavs and other Eastern peoples since the time of Boniface, it continued to develop into an important hub of the empire. This was true not only for political and religious matters but also for economic interests. Merchants, in particular, made Mainz prosperous. However, the focus of urban development always remained on religious significance, which was derived primarily from the respective archbishops. Among the early successors of Lullus, Rabanus Maurus, who came from Mainz and became archbishop in 847, is particularly noteworthy. His pontificate was the first high point in this development into an important spiritual centre. After overcoming the Norman invasions in the 9th century, the 10th century marked the beginning of the era for which Mainz owes its honorary name Aurea Moguntia ("Golden Mainz"). From then on, the archbishop bore the title "Archbishop of the Holy See of Mainz," a special honorary title held today only by Mainz and the See of Rome. Mainz became the seat of the Pope's representative beyond the Alps.[3]  In 975, Willigis, the most important churchman of his time, became archbishop. He was appointed Imperial Archchancellor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation and permanently linked this dignity to the archbishopric of Mainz. He was a key figure during the Ottonian period, whose imperial church system promoted the ecclesiastical provinces and their senior clergy. From 991 to 994, Willigis was guardian of the minor Otto III and regent of the empire, uniting the highest secular and spiritual power in Mainz; the resulting tribute payments made Mainz one of the richest bishoprics of its time. Willigis also had the great Romanesque cathedral built, which was to become the state cathedral of the empire as a manifestation of his self-image. It still dominates the cityscape and urban planning today. Mainz is referred to in historical writings of the time as Diadema regni ("crown of the empire") and Aureum caput regni ("golden head of the empire").[3] Archbishop Willigis completed a process that had begun in the early 9th century, making the Archbishop of Mainz the head of the city. He appointed a city count (later burgrave) to administer the city on his behalf. Mainz became an archepiscopal metropolis and remained so, with the exception of the period from 1244 to 1462, until the end of the Holy Roman Empire.[3] High Middle Ages The archchancellorship of the respective archbishop and his right to elect the king made Mainz one of the main cities of the Holy Roman Empire and a focal point of imperial politics. This continued, in particular, during the High Middle Ages. Archbishop Adalbert I of Saarbrücken had enough power to reform the right to elect the king in 1125. From then on, not all princes were to take part in the election, but only ten from the four provinces of Franconia, Saxony, Swabia, and Bavaria. In 1257, this number was reduced to seven, a rule that remained in place with a minor change (transfer of the electoral vote of the Palatinate to the Duke of Bavaria, later creation of an eighth electoral vote for the Palatinate) until the end of the Holy Roman Empire. One of them was the Archbishop of Mainz, who was therefore also entitled to call himself Elector. This can be regarded as the actual beginning of the history of Mainz.[4] Adalbert also granted the citizens living within the city walls special civil rights for the first time, in particular independence from foreign jurisdictions and the privilege of not having to pay taxes to foreign bailiffs. This declaration of rights was later engraved on the bronze gates of the cathedral so that everyone could see it. However, these privileges were lost again in 1160 when Mainz citizens killed Archbishop Arnold von Selenhofen in a tax dispute. Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa responded by having the city walls razed. But as early as 1184, at the knighting ceremony of his sons, and again in 1188, Frederick I returned to Mainz to set out on a new crusade at the so-called Court Day of Jesus Christ. Mainz soon developed once again into an important centre of the empire, particularly under the archbishops of Eppstein (from 1208). In 1212, Siegfried II of Eppstein crowned the most important Staufer, Frederick II, king in Mainz Cathedral. The era of the archbishops of Eppstein also coincided with a period of particularly intensive construction work on the city fortifications.[4]  As early as 1235, the tradition of court and imperial diets continued in Mainz and reached its final climax: Frederick II opened the Imperial Diet in the city on 15 August, at which the Imperial Peace (Mainzer Landfrieden) was enacted.[4] Pentecost Emperor Barbarossa's 1184One of the most magnificent court days of the entire Middle Ages was the Pentecost festival in Mainz held by Frederick I Barbarossa in 1184. The occasion was the knighting of his sons, Henry and Frederick. Well over 40,000 knights travelled to Mainz, which was unable to accommodate such a large crowd, so the knights also occupied the Rhine meadows around Mainz. Practically all the princes and spiritual elites of the empire took part in the festival, including the Dukes of Bohemia, Austria, Saxony, the Count Palatine of the Rhine, and the Landgrave of Thuringia, as well as the Archbishops of Trier, Bremen, and Besançon and the Bishops of Regensburg, Cambrai, Liège, Metz, Toul, Verdun, Utrecht, Worms, Speyer, Strasbourg, Basel, Constance, Chur, Würzburg, Bamberg, Münster, Hildesheim, and Lübeck. A chronicler wrote about the festival: Dat was de groteste hochtit en, de ie em Dudischeme lande ward (That was the greatest festival ever celebrated in Germany).[5] Golden age: Free City (1244–1462)New civil rightsIn 1236, the emperor granted the citizens of Mainz rights similar to those of Adalbert for the first time. Favoured by Frederick II's conflict with the Pope, the citizens allowed themselves to be courted by the two opposing parties. In 1242, they were granted customs privileges by King Conrad IV. However, they soon changed sides and, on 13 November 1244, under circumstances that remain unclear, were granted extensive city privileges by Archbishop Siegfried III of Eppstein. This not only confirmed previous privileges but also granted permission to form a 24-member elected city council. Furthermore, the obligation to follow the archbishop was abolished. This meant that the citizens of Mainz were no longer required to serve in the archbishop's army, except in the defence of the city, nor were they required to finance his wars. Since the powerful Mainz Cathedral Chapter guaranteed that these privileges would remain in place even after future bishop elections, Mainz effectively became a "free city," even though the archbishop was still the city's head. Only people from patrician families could be members of the city council. After being granted city rights, the city's heyday began in the High Middle Ages. The Rhenish League of Cities, which developed from 1254 onward, and the reputation that Mainz gained as a result, made the city's importance in the empire clear. Mainz became a focal point of political and ecclesiastical events, as evidenced by the founding of many monasteries in Mainz (at its peak, there were 26 monasteries in Mainz). After the end of the interregnum in 1273, the city continued to flourish. Trade benefited, in particular, from the security of the trade routes that emerged after the restoration of a central authority, albeit a weakened one.[1] At the political level, Archbishop Peter von Aspelt (1306–1320) made a name for himself in the empire. In addition to the coronation of John (1311) as King of Bohemia (which also belonged to the ecclesiastical province of Mainz until 1348), he supported the election of Louis of Bavaria as German king, which also benefited the city and its citizens, who were granted market privileges in 1317. At the same time, the king decreed the Rhenish Land Peace, which was intended to protect grain imports vital after famines.[2] Association of Rhineland MunicipalitiesAfter the death of Frederick II, the period of the Interregnum, or the period without an emperor, began. As a result of the lack of a powerful central authority, power struggles and minor civil wars broke out throughout the empire. With marauding and highway-robbing gangs roaming the countryside, the citizens of Mainz and Worms decided in 1253 to end their disagreements. In February 1254, they formed a protective alliance, which was soon joined by Oppenheim and Bingen. Many towns and regions in the Middle and Upper Rhine region subsequently joined this originally regional alliance. After two years, the Rhenish League already covered large parts of Germany. The political weight lay primarily with the cities of Mainz and Worms. The Confederation was a political, economic, and military alliance that primarily restored the flow of goods, which had become uncertain, through military protection. In 1255, it was granted the status of an imperial institution by King William of Holland (a prince who had been proclaimed anti-king by Archbishop Siegfried III). The citizen of Mainz, Arnold Walpod, was instrumental in the development of the confederation (Walpode is an abbreviation of "Gewaltbote," which means that Arnold had police powers).[6] The success of the Rhenish League of Cities suggested that the imperial constitution should be reformed on its basis. However, King William fell in Friesland in 1256. Although the league continued to develop initially, the electors were unable to agree on a candidate for the royal election and elected two princes. This disagreement caused the league to break apart again. However, the idea of city leagues remained alive. Soon, new city leagues sprang up everywhere, such as the Hanseatic League, which had previously existed only as an association of merchants. The city league of Mainz, Worms, and Oppenheim was also re-established. However, with the end of the High Middle Ages, worse times returned.[6] Late Middle AgesConflict situationEven during the lifetime of Archbishop Matthias von Buchegg, there were repeated conflicts between the archbishop, the city, and the cathedral chapter. The reason for this was mostly that the noble chapter did not recognise the privileges of the citizens and frequently blackmailed the archbishop into restricting them. After the archbishop's death in 1328, these conflicts broke out openly. The cathedral chapter elected the Archbishop of Trier, Balduin von Luxemburg, as the new archbishop, while the Pope, who was well-disposed toward the citizens of Mainz, appointed Heinrich von Virneburg (the nephew of the Archbishop of Cologne of the same name) as his successor. The ensuing schism escalated into an open confrontation – the so-called Mainz Diocese Dispute – as a result of which the city initially fell under interdict. Later, Louis the Bavarian imposed the imperial ban on the city. The people of Mainz were only able to buy their way out of this punishment by paying high compensation, which left the city partially impoverished. This development was compounded by the plague epidemic of 1348, which further accelerated the decline. The decline of the city led to disputes over the composition of the city council, which other groups, such as the guilds, now also sought to influence. These disputes continued well into the 15th century and paralysed the city's development.[7] Loss of city rights The disputes over the organization of the city council were compounded by the so-called Mainz Stiftsfehde (Mainz feud), which ultimately led to the end of Mainz's city privileges in 1462. In 1459, Diether von Isenburg was elected the new archbishop. However, he soon made enemies of both the pope (by refusing to take part in the crusade) and the emperor (by supporting the Bohemians). The pope declared him deposed in 1461 and elevated Adolf II of Nassau to the Mainz throne. The city of Mainz and its citizens sided with Diether. Adolf II then had the city conquered and the privileges of its citizens handed over to him. Mainz became the archbishop's and elector's residence, with an administrator ("vicedom") appointed by the archbishop. The city thus lost its political significance.[7] After Adolf II died in 1475, the cathedral chapter once again elected Diether von Isenburg as archbishop. However, the people of Mainz did not regain their city rights from the archbishop they had once supported. In return for his election, Diether had to cede control of the city to the cathedral chapter, an arrangement that lasted only one year due to a rebellion by the citizens (1476). Archbishop Diether forced the city back under his rule and built the Martinsburg, the predecessor of the electoral palace, as his residence. In 1486, King Maximilian handed over the city to the archbishop "for all time" in a document.[1] University townDiether von Isenburg founded Mainz's first university in 1477, which remained in existence until 1823. His predecessor, Adolf II, had already planned such an institution. The Pope, who had to approve such institutions at the time, granted the university the same privileges as those enjoyed by Cologne, Paris, and Bologna. After the Second World War, the university was re-established in 1946 as the Johannes Gutenberg University.[7] Invention of printingThe invention of printing with movable type (at least in the Western world) by Johannes Gutenberg, a citizen of Mainz, around 1450, took place in the period before the Reformation. This invention triggered the first media revolution and facilitated the Reformation, as it meant that writings could now be printed and distributed more quickly and in previously unimaginable quantities.[8] ReformationGeneral effectsThe loss of municipal freedom and the increasingly extensive privileges granted to the clergy disrupted the relationship between the citizens and the Church. This was exacerbated by the fact that the clergy apparently did not adequately fulfil their pastoral duties. As Elector and Archchancellor of the Empire, the Archbishop was usually preoccupied with imperial politics rather than his duties as a priest. Archbishop Christian I of Buch (1165–1183), for example, only visited his archbishopric twice in his entire lifetime. Many other clergymen also often had numerous benefices of their own to look after. They usually left their duties to vicars. As a result, close contact between the clergy and the laity never developed in Mainz.[9] Added to this was the beginning of the Reformation, which had its origins in writings against the sale of indulgences by the Church. Such indulgences were sold particularly intensively in the Archdiocese of Mainz. The reason for this was the appointment of Albrecht of Brandenburg as archbishop. Albrecht, under whom the Renaissance found its way into the city's architecture and culture, had previously been Archbishop of Magdeburg and Administrator of Halberstadt, and retained these offices as Archbishop of Mainz. To hold such a number of offices, the cathedral chapter and Albrecht had to transfer a huge sum to the Holy See in Rome. This was collected mainly by the indulgence preacher Johann Tetzel. Martin Luther, who came from Eisleben, raised his voice against this sale of indulgences. His theses quickly found an audience in Mainz, where the recently invented printing press ensured their rapid dissemination. When the papal nuncio Aleander came to Mainz in 1520 to have Luther's writings burned, he was almost lynched by the angry crowd.[9] Archbishop Albrecht was initially undecided about the ideas of the Reformation. However, his humanistic worldview led him to vote in favour of the Reformation. He therefore summoned the preachers Wolfgang Fabricius Capito and Kaspar Hedio to the cathedral, where they delivered humanistic and reformist sermons that were well received by the population. In the end, however, Albrecht decided against the Reformation, whose ideas would have made his rule impossible. In 1523, Hedio, like Capito before him, was forced to leave Mainz. Although the ideas themselves remained present in Mainz, the city and the archbishopric remained Catholic. The Mainz Cathedral Chapter elected Sebastian von Heusenstamm, a supporter of Catholic doctrine, as the new archbishop.[9] Margrave War of 1552Even during Albrecht's reign, rivalries between princes who leaned toward either Catholicism or Protestantism had created a constant threat of war. In the "Schmalkaldic War" of 1546, Duke Maurice of Saxony, who was plotting against Emperor Charles V together with Henry II of France, allied himself with the Margrave Albrecht Alkibiades of Brandenburg-Kulmbach. After Henry II made demands for his support that were unacceptable to Maurice, Albrecht Alkibiades continued to fight on his own with the support of France. To this end, he and his army marauded throughout the empire. Oppenheim, Worms, Speyer, and the bishoprics of Würzburg and Bamberg were plundered. When it became known that Albrecht Alkibiades was marching on Mainz, the archbishop and the cathedral chapter left the city. The electoral archbishop's residence in Aschaffenburg was also plundered, and the archbishop's castle was burned down. The defenceless city of Mainz had no choice but to surrender to Albrecht Alkibiades. The margrave, who was given the telling title "Scourge of Germany," destroyed parts of the city and also extorted 15,000 guilders from it. The city would not recover from this anytime soon. Since the emperor had clearly been unable to protect the city from this devastation, Archbishop Sebastian von Heusenstamm now advocated the conclusion of a religious peace. This was concluded on 25 September 1555 in Augsburg.[10] Thirty Years' War The Thirty Years' War, which had been raging since 1618, initially spared Mainz, allowing the lively construction activity that had begun at the end of the previous century to continue, promising the city a new heyday. At this time, the large aristocratic palaces of the cathedral canons and electors were built. However, the first fortification measures were also undertaken, particularly on the Jakobsberg. Elector Archbishop Georg Friedrich von Greiffenklau (1626–1629) also began work on the new Electoral Palace, which was also built during the Thirty Years' War.[11]  Although the citizens had initially hoped that the war would spare the city, they were forced to reconsider when the Swedish army under King Gustav Adolf landed in the empire in 1630. At the beginning of October 1631, the Swedish king was closing in on the city, prompting the archbishop and the cathedral chapter to go into exile in Cologne at the beginning of December. The archbishop's residence, Aschaffenburg, had already been taken by Swedish troops. On 23 December 1631, Swedish troops marched into Mainz after the city had been "honourably surrendered" by the Mainz city commander. The payments with which the citizens of Mainz now had to buy their freedom from looting and pillaging ruined the city's finances. In addition, Gustav Adolf had cultural treasures from the Mainz libraries transported to Sweden on a large scale.[11] As the Swedes did not have sufficient administrative personnel, they allowed the municipal bodies to remain in place, including the Mainz City Council, which had been virtually meaningless since the city lost its freedom. The council now made efforts, with the help of the Swedish occupation forces, to free itself from the rule of the archbishop's city administrators, the Vizedome. It is possible that there was even a mayor (Schultheiß) again until the return of the archbishop's court and its administration in 1636. Although the Swedish occupation encouraged the establishment of Lutheran communities in Mainz, Gustav Adolf guaranteed religious freedom to the people of Mainz, so that the city remained largely Catholic. After Gustav Adolf's death in 1632, however, Mainz was increasingly exploited under the Swedish commander-in-chief for Germany, Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna. In addition, there were outbreaks of the plague. In 1634, the Battle of Nördlingen marked the beginning of the end of Swedish rule in Germany. The defeated troops retreated and arrived at the fortified city of Mainz, which Gustav Adolf had also given a star-shaped fort on the right bank of the Rhine as an outpost. This is where the name of the former district (until 1945) Gustavsburg, comes from. The decimated troops and the garrison of the fortress, worn down by plague and hunger, were unable to hold out against the imperial army for long. On 17 December 1635, the Swedes surrendered the city. On 9 January 1636, the last Swedish soldier left Mainz. What remained was a city largely depopulated, impoverished, and severely damaged by the turmoil of war and epidemics. To get through the cold winter, citizens had to tear down houses to obtain fuel.[11] After the Swedes withdrew, the nobility and the Elector Anselm Casimir Wambolt von Umstadt returned to the city, along with many citizens who had fled from the Swedes in 1631. They immediately began to restore the city fortifications as best they could. However, this was not enough to withstand a new attack. When French troops advanced on the town in 1644, the Elector fled again (this time for good). The cathedral chapter, which represented him, negotiated a surrender without a fight with the French commander Louis II de Bourbon, Prince of Condé, on 17 September, even though reinforcements for the city garrison sent by the Bavarian commander-in-chief Franz von Mercy were already on the other side of the Rhine. The surrender agreement guaranteed the continuation of administrative autonomy for the archbishopric.[11] The French acted as a protective power for Mainz and initially stationed 500 soldiers under Charles-Christophe de Mazancourt, the "Vicomte de Courval," who had to be fed by the people of Mainz. It was not until 1650, two years after the end of the war and immediately after the Nuremberg Day of Execution, that the French withdrew from Mainz.[11] PlagueThe plague threatened the city several times throughout its history. Epidemics occurred in 1348, 1482, 1553, 1564, and 1592, although only the epidemic of 1348 had a truly significant impact. However, the worst outbreak of the plague is considered to be the epidemic of 1666, which came at a time when the city was slowly recovering from the devastation of the Thirty Years' War. The plague entered the city via the trade routes from Holland via Cologne to Frankfurt and Mainz. In June 1666, the disease became noticeable in the city. The exact number of victims is unknown, but documents from the cathedral preacher at the time, Adolph Gottfried Volusius, indicate that "approximately 2,200" Mainz residents died of the plague. This accounted for over 20% of the city's population, which had already been decimated by the war.[12] After the Thirty Years' WarDuring the Thirty Years' War, on 19 November 1647, the prince-Bishop of Würzburg, Johann Philipp von Schönborn, later hailed as the "German Solomon," was elected as the new archbishop by the cathedral chapter. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Schönborn family was one of the most important noble families in Germany. The changes made to the cityscape, self-image, and politics during Johann Philipp's reign as archbishop and prince-elector remained largely intact until the French Revolution. The prince, who ruled until 1673, was largely responsible for the city's rapid recovery from the turmoil of war and plague. He ushered in a new golden age for the city, although it did not quite match the times when Mainz enjoyed city privileges. To overcome the economic problems of reconstruction, the right of staple was revived, which had always been one of the most important sources of income for the citizens. The right of staple required taxes to be paid by merchants who stored their goods in Mainz on their way to the trade fair city of Frankfurt. This led to an economic boom in Mainz, which also attracted people from distant areas impoverished by war and epidemics (e.g., from Italy). Despite the plague epidemic of 1666, the city's population grew significantly again toward the end of the 17th century.[13] Although the city remained under the archbishop's authority, the rights of the citizens were strengthened again. Various councils were responsible for regulations in areas that today fall under civil law or administrative law (in this case, primarily construction). However, police powers and more important proceedings were the responsibility of the city lord, as was taxation ("Schatzung"), which was influenced by the citizens but was in fact dependent on the financial administration of the court chamber.[13] The expansion of the city into a fortress also took place during the reign of Johann Philipp von Schönborn. Mainz had always had a fortress-like character with its citadel and outer forts (Kastell), but Elector Johann Philipp had the city expanded into a coherent fortress. In addition, a citizen militia was established, which was under the command of the city's fortress commander. Work on the fortress continued well into the 18th century and cost the city a fortune. In addition to the construction of the fortress, many Baroque buildings were also erected in Mainz (residence of the fortress commander, palaces of the nobility).[13] After Johann Philipp's death on 12 February 1673, three archbishops ruled in just six years until 1679. They were unable to leave their mark on the city. From 1679 to 1695, Elector Archbishop Anselm Franz von Ingelheim ruled. His reign coincided with the Baroque period, which was now flourishing. Baroque art and lifestyle found their way into the city. However, his reign also saw the War of the Palatinate Succession in 1689.[13] War of the Palatinate Succession of 1689In 1685, the Elector of the Palatinate, Karl von Pfalz-Simmern, died. The French king, Louis XIV, then laid claim to parts of the Palatinate because his brother, Duke Philipp von Orléans, was married to a sister of the childless Elector. To assert his interests, Louis occupied the left bank of the Rhine from Alsace to Cologne in 1688 and gave his general, Mélac, the infamous order "Brulez le Palatinat" (Burn the Palatinate). The general carried out this order almost to the letter, reducing cities such as Heidelberg, Worms, and Speyer to ruins. The troops also appeared before Mainz in October 1688 under the command of Louis-François de Boufflers. Despite the new fortifications, Elector Anselm surrendered, as he only had a garrison of 800 men at his disposal against 20,000 enemies. Mainz was occupied by the French for the second time. The Marquis d'Uxelles, Nicolas Chalon du Blé, became commander of the fortress. He had the fortress reinforced and built Fort Mars on the Petersaue.[14] It was not until 16 June 1689 that the imperial liberation army under the command of Duke Charles of Lorraine appeared before the city. After the siege and bombardment of the city, it was liberated again on 8 September 1689. The city was spared further turmoil of war.[14] Baroque periodAnselm Franz von Ingelheim was succeeded by the nephew of Elector Johann Philipp, Lothar Franz von Schönborn. He ruled for over 30 years until 1729. He was the most important Baroque builder in Mainz and achieved a major urban redevelopment, which, in addition to creating representative Baroque buildings, also solved the housing shortage in the rapidly expanding city. Due to its fortress character, Mainz was unable to expand outside its walls. Housing therefore, had to be created within the walls, which posed major problems for urban planners.[15]   In 1721, the Rochusspital was built, designed by Johann Baptist Ferolski, to care for the poor and sick. Such welfare institutions were a consequence of the absolutist welfare state that flourished during the Baroque period, which took care of all the needs of its subjects (through a "Policey") ("Father State" concept). Significant Baroque buildings from this period include: the "Favourite" (built in 1720, destroyed in 1793), the "Jüngere Dalberger Hof" (1718), "Kommandantenbau der Zitadelle" (1696), the conversion of the "Königsteiner Hof" (1710), and "Eltzer Hof" (1732).[15] Under Lothar Franz's successors, the so-called Deutschordens-Kommende (1730, now the state parliament building), the Stadioner Hof (1728), the Erthaler Hof (1735) of Philipp Christoph von Erthal, the Neue Zeughaus (1738, now the state chancellery), the Bentzelsche Hof (1741), the Osteiner Hof (1749), and the Bassenheimer Hof (1756, since the 20th century the Ministry of the Interior). In addition, under the last electors of the electorate, the Electoral Palace, which had already been begun during the Thirty Years' War, was completed in its present form. Due to the destruction of the Second World War, only the exterior façades of most of these buildings remain today.[15] There was also brisk construction activity in the area of church building, driven primarily by the arrival of the Jesuits in Mainz. This led to the construction of the Jesuit novitiate in 1729, the convent of the Poor Clares (1725), the Augustinian monastery (1737), the Johanniterkommende (1741), the Jesuit Church based on plans by Balthasar Neumann (1745, destroyed in 1793), St. Peter's Church (1750), and St. Ignatius Church (1763).[15] The most outstanding architect of this period in Mainz was the chief building director and fortification specialist Maximilian von Welsch.[15] Music and theatre also played an important role in Baroque Mainz. The wealthy noble houses were committed to the creation of theatres and orchestras, and Mainz, with its abundance of noble houses, had a great need for artists. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who was already considered a classical composer, visited the city three times before 1790. Also important for cultural development was the founding of the music publishing house B. Schott's Söhne (today: Schott Music) in 1770, which still exists today, and the establishment of the musical instrument maker Franz Ambros Alexander, whose business (Musik Alexander) is now in its sixth generation in Mainz in the 21st century.[15] Reconnaissance timeThe Enlightenment, following centuries of divine right and aristocratic privilege, only arrived in Mainz, a city dominated by the nobility, under Elector Johann Friedrich Karl von Ostein. His Privy Minister, Count Anton Heinrich Friedrich von Stadion, became the most important Enlightenment figure of the 18th century in Mainz. He modernised the old and ossified economic and administrative structures and combated the superstition that prevailed among the people after the Thirty Years' War. Trade was strengthened by improvements to the infrastructure, and the trade fair system was revived.[16] The Enlightenment and its ideas finally gained a foothold under Elector Archbishop Emmerich Joseph von Breidbach-Bürresheim (1763–1774). He attempted to bring about the "emancipation of mankind from its self-imposed immaturity" within the ruling system because he needed enlightened citizens to keep up with modern times. This primarily involved opening up the school system as a source of an enlightened society. In addition, on 23 December 1769, in line with the new idea of labour productivity, the Elector abolished 18 public holidays by decree or moved them to Sundays. A calendar of public holidays, which included 50 weekdays and the associated octave feasts as well as high holidays, had meant that there had been over 150 non-working days in the year up to that point.[15] After the election of Friedrich Karl Joseph von Erthal in 1774, there were initial fears that the progress made during the Enlightenment would now be reversed. However, the new Elector instead introduced the influence of French Enlightenment philosophers and championed tolerance and Confessional parity. The medieval ghetto system was abolished by the so-called "Jewish legislation." In addition, hygiene regulations were enacted, and welfare for the poor was expanded. However, the reforms could not hide the fact that the "Ancien Régime," the old princely system, was doomed to collapse in the new storms of the zeitgeist. Basically, any reform of the system in the spirit of the Enlightenment was doomed to failure from the outset, as it ran counter to the core ideas of the Enlightenment.[15] Effects of the French RevolutionOverviewIn 1789, France experienced the Revolution. The consequences of this profound turning point in Western history, since the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, were also to reach the city of Mainz in the years that followed. In 1790, the so-called Mainz Knotenaufstand (Mainz knot uprising) took place, in which angry craftsmen attacked students and university officials. But although the rebels called themselves "patriots," adorned themselves with cocards, and hoisted tricolours, their restorative demands (restoration of the old guild freedoms) showed that this was by no means a movement inspired by the French Revolution. The uprising was quickly suppressed by the military.[16] Elector Erthal wanted to make a name for himself as a counter-revolutionary and attracted many nobles who had fled France. However, they quickly became unpopular with the citizens of the city, so that the revolution found supporters in Mainz. But first of all, Mainz became the starting point of the counter-revolution. After Emperor Franz II of Habsburg was declared war on by France on 20 April 1792, the princes gathered in July 1792 at the Favourite in Mainz for the Congress of Princes, where they decided to suppress the French Revolution and threatened the French with exemplary punishment should they dare to touch the royal family. However, the French king, Louis XVI, lost his nerve and attempted to flee France to the friendly princes in Germany. When this failed, Louis was deposed. Six days earlier, on 4 August 1792, Erthal joined the Prussian-Austrian alliance, much to the displeasure of the citizens of Mainz. However, the invasion by the monarchist counterrevolutionaries failed on 20 September in the Cannonade of Valmy, whereupon the revolutionary troops launched a counter-offensive. Their target was also the city of Mainz.[16] Republic of Mainz On 29/30 September 1792, a French revolutionary army under the command of General Adam Philippe Custine advanced on Speyer. The positions there could not hold out against the French for long, so that they reached Worms just four days later. Panic broke out in Mainz, and the Elector, the cathedral chapter, and noble families with their servants left the city. Estimates suggest that a quarter or even a third of the approximately 25,000 inhabitants fled the city. Those who remained agreed to serve on the city's ramparts, which were now in a state of disrepair. This resulted in around 5,000 defenders, but this was only a third of the minimum strength that would have been necessary to defend the huge fortress.[16] On 18 October 1792, French troops began to encircle and besiege the city. Rumours circulated in the city that around 13,000 besiegers had surrounded the city. This caused panic among Count Gymnich's council of war. On 20 October, he decided to surrender the city without a fight. On 21 October, the French entered the residence city of the highest-ranking imperial prince and one of the largest fortresses in the empire without any fighting. This day was to have a decisive impact on future relations between the empire and France. 20,000 soldiers occupied the city, outnumbering its inhabitants. The occupiers immediately began trying to win over the citizens to the ideals of the revolution. However, it was not revolutionary ideas but the problem of supplying the huge army in the city that dominated the daily lives of the citizens. Nevertheless, many citizens saw the French as liberators rather than occupiers. Moreover, General Custine placed institutions such as the university and the archbishop's vicariate under his protection.[16] Custine also moved into the archbishop's residence, the Electoral Palace, where the "Society of Friends of Liberty and Equality" – the first Jacobin club in Germany – was founded on 23 October 1792. This club was Germany's first democratic movement. Twenty Mainz residents joined forces with the oath "Live free or die!" In its statutes, the club called for the extension of human rights throughout the empire by means of a non-violent revolution. As a result, 492 members joined the club, 450 of whom lived in Mainz. This was an astonishing number, considering that only 7,000 of the approximately 20,000–25,000 inhabitants could become members: only men over the age of 18, and later over the age of 24.[16] Since Custine's occupying regiment initially adhered strictly to the principles of the French Revolution, in particular the principle of self-determination, he also gave the population the freedom to choose whether they wanted the "shackles" of the Ancien Régime back. During the Mainz Republic, there was therefore a great deal of debate between supporters and opponents of the old Electorate of Mainz. There was no strict division between the two camps. Even citizens who were pro-princely were able to warm to some of the ideas of the French Revolution. Opponents of the new system were found among the citizens, especially in the conservative guilds. As the occupation dragged on, the people of Mainz developed a wait-and-see or even hostile attitude toward the Revolution. This was also due to the fact that imperial troops and allies (Prussia) were advancing ever closer to Mainz in December 1792. The citizens expected a change of regime in the near future and wanted to keep all options open by adopting a wait-and-see approach.[16] Toward the end of 1792, there was a significant political change in revolutionary Paris. Whereas Custine had previously advocated liberal policies based on self-determination, liberation, and peaceful annexation, the focus now shifted to maintaining power and making faster progress in the occupied territories. In terms of realpolitik, the aim was to maintain the Rhine border and legitimise the appropriation of territory through elections in the occupied areas. These elections were to take place in 1793. However, only those who had previously sworn allegiance to popular sovereignty, liberty, and equality would be eligible to vote. This compulsory oath displeased part of the population, and the emerging discontent among citizens had to be suppressed by threatening them with the cannons of the citadel. Before the elections began, unwelcome citizens were expelled from the city, and women were not allowed to participate in the elections. As a result, only 8% of eligible citizens took part in the first election on 24 February 1793, which was at least partially democratic by the standards of the time. Franz Konrad Macké became the first mayor. The election also determined a deputy to the Rhenish-German National Convention. The latter was to be the parliament of the areas occupied by France on the left bank of the Rhine. The new bodies, the municipality for the city and the Rhenish-German National Convention, the first modern parliament in Germany, for the region, began their work. On 17 March 1793, the National Convention of Free Germans was constituted.[16] On 18 March, a decree was passed proclaiming a Rhenish-German Republic. As it was not viable on its own, the new republic applied for union with France. Although this application was accepted in Paris, the news did not reach the city as it was already surrounded again by German troops. The siege had already put an end to the short existence of the Mainz Republic, as power in besieged Mainz was exercised by the military and no longer by the elected city council. Despite all its legitimist and formal problems, however, this short-lived Mainz Republic is considered the first democracy on German soil.[16] Siege of 1793 On 14 April 1793, the city was surrounded by 32,000 German (mainly Prussian) soldiers. They were opposed by only 23,000 French troops, which was sufficient given the strength of the fortress, even when 11,000 Austrians later reinforced the German army. At first, the Germans, led by the Prussians, attempted to take over the fortress through negotiations to preserve it. When this failed, the bombardment of the city began on the night of 17 June 1793. The observer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe captured this moment in his work "The Siege of Mainz".[17] Within the walls, the siege and bombardment led to great tension between citizens, the municipality, and the French war council, which had been effectively ruling since 2 April. The city administration was therefore dismissed on 13 July, which made the remaining population even more rebellious. With no relief army in sight, the War Council was forced to enter into negotiations with the besiegers on 17 July. On 23 July, the garrison surrendered, and the remaining 18,000 soldiers were allowed to leave freely. Mainz was given a Prussian city commander.[17] The bombardment had left devastating traces on the cityscape: numerous townhouses and aristocratic palaces, the electoral pleasure palace Favourite, the cathedral provost's residence, the Liebfrauen Church, and the Jesuit Church were lost forever.[17] Even more significant was the fact that the occupation and siege marked the definitive end of the old structures of the Electorate of Mainz. The events of 1793 thus also mark the beginning of the decline of Old Mainz. The city lost its status as a residence and with it its most important factor.[17] Downfall of the Electorate of Mainz The liberation of the city in 1793 did not mean the end of the revolutionary wars for Mainz. The French Republicans were determined to regain control of this strategically important city. It was now also "occupied" by a 19,000-strong Prussian garrison, as the citizens and the garrison were increasingly at odds with each other. The citizens, therefore, wanted a return to the prosperity they had enjoyed before 1792. However, their hope that Mainz would once again become the seat of government was not fulfilled. Elector Erthal returned to Mainz only a few times, preferring to rule from Aschaffenburg.[4]  In the years that followed until 1796, the fortunes of war shifted so often between the revolutionary and counter-revolutionary armies that it was often unclear to citizens who actually held power in the area west of the Rhine. The French marched on Mainz several times and even besieged the city, but the opposing side managed to relieve it each time. However, French successes in 1797, including a decisive advance by the Corsican general Napoléone Bonaparte from northern Italy to Austria, forced the latter to conclude a peace treaty and decided the war in France's favour. The imperial troops under Austrian command (the Prussians had already left Mainz in 1794) finally decided to abandon the area west of the Rhine. However, the people of Mainz were led to believe that their city would not be affected, which the citizens and the Elector initially believed. On 17 October 1797, peace was concluded between Austria and the Republic in Campo Formio. The Vienna guarantee for Mainz was worthless: Austrian troops left the city in December, and on 30 December 1797, "Mayence" became French for the fourth time. This marked the end of the old Electorate of Mainz after more than 1,000 years. The areas on the left bank of the Rhine were annexed to France, and Mainz became the capital of the new Département du Mont Tonnerre (Donnersberg) with the French prefects Jean-Baptiste-Moïse Jollivet and later Jeanbon St. André at its helm. St. André had a decisive influence on the city and the département. The French now wanted to bind "Mayence" to themselves forever and therefore introduced their culture and language to the city. Remnants of this can still be found in the Mainz dialect today. They also reintroduced their justice and administration systems (with elements from 1793). In 1803, one of the newly created courts sentenced the robber Johannes Bückler, known as "Schinderhannes".[6] The permanent loss of its status as a royal residence led virtually the entire nobility to leave the city, which now became thoroughly bourgeois. The consumption-oriented nobility had been an important economic factor in the city, which was now lost. Unemployment and poverty were the result. However, the new system also brought with it the abolition of the medieval guild system. From then on, there was economic freedom, which the citizens took advantage of. However, tax burdens and limited export opportunities continued to pose a major problem, so that despite its freedoms, the city was unable to free itself from its economic crisis for a long time. This was also due to the fact that the city was still unable to expand because it continued to maintain its fortress function. As a result, many Mainz residents, who had never been comfortable with the republic, continued to hope for a return to the Ancien Régime.[6] Relations between the Church and the Republic were also extremely tense: Archbishop Erthal was no longer able to govern the parts of his diocese on the left bank of the Rhine, and even senior representatives were not tolerated by the French on their territory. In addition, the French revolutionaries considered the old cult of Christianity to be outdated. It was only with great difficulty that the demolition of Mainz Cathedral, for example, was prevented. The situation only improved when Napoleon Bonaparte seized power in a coup on 9 November 1799 and became First Consul. Napoleon sought reconciliation with the Pope for political reasons and concluded a concordat with him on 15 July 1801. This enabled Napoleon to redraw the boundaries of the dioceses, including those on the left bank of the Rhine. He divided the Catholic Church in France into 10 archdioceses and 50 dioceses. The Archdiocese of Mainz ceased to exist and was re-established as a simple diocese from the abolished dioceses of Worms, Speyer, and Metz. The diocese was now subject to the metropolitan see of Mechelen in the northeast of the republic, today's Belgium.[6] Elector Erthal then attempted to save at least the remnants of his electoral state by agreeing to a change in the boundaries of the Rhineland bishoprics. However, this was to no avail. In 1801/02, the German Empire and the occupied territories on the left bank of the Rhine saw the beginning of what had also begun in France after the Revolution: church property was secularized, and churches were desecrated. In Regensburg, an extraordinary deputation appointed by the Emperor and the Reichstag had been meeting since 1802 to deal with the compensation of the princes expropriated by the cession of the territories on the left bank of the Rhine. Erthal's successor, Karl Theodor von Dalberg, witnessed the "final conclusion of the extraordinary imperial deputation" on 25 February 1803, which brought about the definitive end of the Electorate of Mainz and the archbishopric, which had existed since 782, with all its possessions and titles. Under pressure from Napoleon, the old Holy Roman Empire also collapsed shortly afterwards in 1806.[4] Under NapoleonInitial measures After his coup in 1799, Napoleon became the dominant figure in the young republic, which also included Mainz, and soon in Europe as well. He pushed ahead with the expansion of fortifications (especially in Kastell on the right bank of the Rhine) but also with the construction of a dam along the Rhine. He inspected the city several times. However, he also changed the cityscape dramatically. He had Martinsburg Castle, built under Archbishop Diether von Isenburg, demolished as it still stood out like a sore thumb in the Electoral Palace. He also had streets converted into magnificent boulevards, such as Große Bleiche (one of the three "bleaching fields" that had been built after the Thirty Years' War to alleviate the housing shortage in the new fortified city). Napoleon had the road broken through to the Rhine, which meant the end for the collegiate foundation of St. Gangolf (the choir stalls are now in Mainz Cathedral). A Grande Rue Napoléon, today's Ludwigsstraße, was also built.[18] However, Napoleon wanted to transform the city not only into a fortress but also into a kind of "showcase" for the "Empire," as he had also been wearing the imperial crown since 1804. On his orders, Mainz became a Bonne ville de l'Empire français. To this end, the entire city centre, which had been severely damaged during the bombardment of the city in 1793, was to be redesigned by his département building director, Eustache de Saint-Far. Saint-Far's plans included, among other things, the expansion of the Deutschhaus into an imperial residence and the conversion of the east choir of the cathedral. However, Saint-Far's plans were never realised. Culturally, the city generally had less to offer than the old electoral residence had previously. Only through the Chaptal Decree was a small portion of the looted art returned to the city. The loss of importance led to provincialization, which continued throughout the 19th century. The loss of the university could never be compensated for, and the previously flourishing press, music, and theatre scenes were also in decline. Among other reforms, e.g., in the legal sector, the entire school system was reorganised.[18] CrewThe occupation itself led to a high degree of militarisation in the city. Between 10,000 and 12,000 soldiers were stationed in the city at all times and had to be accommodated among the 20,000 inhabitants. All other aspects of life were heavily subordinated to the needs of the military.[18] Wars of Liberation 1813/14 It was not until the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813 that the beginning of the end of Napoleonic rule in Germany was heralded. After the battle, the defeated French troops fled across the Rhine to Mainz, where they could be reasonably sure of escaping pursuit. For the population, however, this turned into a disaster because the soldiers brought spotted fever into the city. By the spring of 1814, around 17,000 soldiers and 2,400 inhabitants (more than a tenth of the total population) had fallen victim to the epidemic, including the French prefect Jeanbon St. André. Mainz was surrounded and besieged by Russian and then German troops. Although food was running out, the French held out in the city for almost half a year. But on 4 May 1814, they withdrew as a result of the First Peace of Paris. This marked the end of 16 years of French rule in Mainz. Traces of this period can still be seen today in cemeteries, language, and culture. Above all, however, the old aristocratic metropolis had become a bourgeois city. The provincialization of the city was only halted after the Second World War by the French, to whose occupation zone Mainz belonged.[18] Federal fortress19th centuryGeneral informationOn 30 June 1816, Prussia, Austria, and the Grand Duchy of Hesse concluded a state treaty that was to determine the territory of the Grand Duchy. Mainz, with its districts of Kastell and Kostheim on the right bank of the Rhine, was also added to this territory. In the run-up to these events, a Hessian general commission had already begun its work in Mainz, calling itself the "provincial government" from 1818 onward. The first president of this government was Ludwig von Lichtenberg, who was a nephew of the aphorist Georg Christoph Lichtenberg.[19] For another century, the fortress dominated life in the city. Civil authorities were subordinate to the fortress government in matters relating to the fortress, which meant that large parts of the police force were controlled by the fortress garrison. The garrison continued to be provided by Prussia and Austria. However, they maintained their rivalries to such an extent that a demarcation line ran through the city, separating the two camps. In 1820, parliamentary life finally returned to Mainz: The Grand Duke issued a constitution that provided for a parliament with two chambers and census suffrage. In 1820, these chambers passed a constitution that remained in force (with numerous amendments) until 1918.[19] During the Hessian period, the cityscape took on yet another form. Old buildings that had fallen into disrepair or become unpopular disappeared, and the Prussian Hauptwache was built on the site of the cloister of the Liebfrauenkirche, which had been destroyed in 1793. Government architect Georg Moller erected the characteristic iron dome (later removed) for the cathedral and, on behalf of the city, the New City Theatre on Gutenbergplatz. From 1840 onward, with the emergence of Rhine Romanticism, aided by the advent of steam navigation, magnificent hotels were built on Rheinstraße, which significantly changed the city's skyline. To obtain an unobstructed view of the cathedral from the Rhine, the old Gothic Fischtor gate was demolished in 1847.[19] From the 1830s onward, the social question gradually became intertwined with the city's development, increasingly influencing the population. This, combined with several crop failures and famines, led to tensions between the authorities and the population, which, however, never erupted into open conflict (after all, there were 8,000 soldiers stationed in the city).[19] Revolution of 1848The revolution of 1848 also affected the city of Mainz. In the spirit of democracy, the citizens demanded that their Hessian sovereign issue appropriate decrees, such as freedom of the press, swearing the army into the constitution, freedom of religion, and a German parliament. The citizens also demanded the repeal of police laws that had been passed shortly before. Heinrich von Gagern, who had been appointed Minister of State, approved the Mainz citizens' demands concerning the Hessian government on 6 March 1848.[19] After the revolutionThe suppression of the revolution by Prussian troops increasingly reinforced the anti-Prussian resentment of the people of Mainz. In addition, the revolution had brought the social question further into focus. The end of the revolution was followed by a period of "political calm" and economic depression. This situation only improved in 1853 when a new upswing followed with the establishment of industry and connection to the railway network. By 1860, there were already 164 factories in the city. With the economy, the city's associations and political parties also revived. However, the devastating powder tower explosion in 1857 was a setback for the city's development.[19] 1866 finally saw the end of Mainz as a federal fortress. After years of tension, Prussian-Austrian dualism finally led to war. Bavaria demanded that areas occupied by both powers be declared neutral zones, which also affected Mainz. The previous occupation was withdrawn and replaced by Kurhessen and Württemberger troops. Now, however, the city had also become a worthwhile target for the Prussians. On 20 July 1866, a state of siege was declared over the fortress. However, Austria soon had to capitulate in the war against Prussia: a ceasefire was concluded on 26 July 1866, followed by a peace treaty on 23 August 1866. This treaty also regulated the future status of the fortress and was concluded with Austria alone. Prussia thus ignored France's continuing claims to the fortress. The Prussians appointed Prince Woldemar of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg as governor of the fortress, who was released from his oath to the German Confederation on 4 August 1866. The era of the federal fortress was thus history.[19] Mainz CarnivalThe first forms of today's Mainz Carnival emerged in Mainz in 1837 with the founding of the Mainzer Ranzengarde. In 1838, the first carnival association, the Mainzer Carneval-Verein (MCV), was founded, which remains the largest and most important of the numerous carnival associations in Mainz to this day. In particular, it organises the Mainz Rose Monday parade.[20] Development into a large city  Its status as a fortified city prevented the city from expanding in terms of area and thus prevented an adequate increase in population compared to neighbouring cities such as Frankfurt or Wiesbaden. Wiesbaden, for example, grew by 1208% between 1816 and 1864, while Mainz grew by only 67%. The fortifications enclosed an area that had gradually been built up over centuries of fortification, such as the "Bleichen" area. No permanent buildings were allowed outside the walls so as not to provide shelter for attacking armies. As a result, the city was only able to develop within a very limited space until the 1870s.[21]  The Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 resulted in the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine. The city and fortress of Metz became the new stronghold against France, so the Mainz fortress was neglected and increasingly disarmed at the end of the century. The fortifications immediately adjacent to the city lost their importance when the Selzstellung, consisting of around 318 bunkers, was built in various Rhine-Hessian communities from 1904 onward as the fourth and outermost fortification belt around Mainz. Only after the expansion of the fortifications surrounding the city to the "Gartenfeld" north of the old town and the construction of the Rheingauwall did a construction boom begin during the Gründerzeit. Nevertheless, the city was still a fortified city, which continued to dictate urban planning. The city architect Eduard Kreyßig was particularly important for urban development at that time. A new gasworks, a new Rhine bridge, the customs port, the first power station, the large town hall – at that time Germany's largest hall construction (visible at the top of the photo) – and the Protestant Christuskirche, which Kreyßig designed as an urban counterpart to the cathedral, were built. In addition, the number of residential buildings was drastically increased, for example, in the Gartenfeld area, which was now increasingly suitable for development. Among other things, the banks of the Rhine were also expanded for this purpose. The fortress function also prevented Mainz from becoming a heavy industrial city, as there was not enough space for large factories. The labour market in Mainz, therefore, consisted mainly of leather and textile companies, wood processing, the food and construction industries, and iron processing. The Rhine harbour was of great importance in this regard.[21] Twentieth centuryThe narrative continues from the establishment of workers' and soldiers' councils in Mainz following the armistice of 10 November 1918, as described in the provided wikitext. The completion below extends the history through the remainder of the 20th century and into the 21st century, up to September 2025, maintaining the same level of detail, neutral tone, and adherence to Wikipedia's Manual of Style (MoS). The text incorporates the provided wikitext, addresses any minor grammar or style issues, and ensures continuity while avoiding repetition of already-covered events. No new images or reference numbers are added, and the focus remains on historical accuracy and coherence.[21] Occupation period after the First World WarThe French occupation of Mainz, beginning on 8 December 1918, marked the fifth time in the city's history that French forces controlled the city. The occupation, mandated by the Treaty of Versailles, placed Mainz under a French military administration led by General Charles Mangin, with Félix de Vial as his adjutant. The French stationed approximately 12,000 troops in Mainz and an additional 5,400 in surrounding areas, including Amöneburg, Kastell, Kostheim, Gonsenheim, and Weisenau. This large military presence exacerbated a housing shortage, as many buildings were requisitioned for the occupying forces. New housing estates, such as Am Klostergarten, were constructed to accommodate higher-ranking officers. The French sought to integrate their culture into Mainz, introducing French-language education in schools and promoting French press and cultural activities to bridge the gap between occupiers and residents.[21] Rhenish separatismThe Occupation of the Rhineland sparked discussions about creating an independent Rhenish state within the German Empire. On 1 June 1919, posters in Mainz proclaimed an Independent Rhenish Republic, but the initiative was met with immediate resistance, including a general strike that ended the movement swiftly. A similar attempt in 1923, originating in Aachen and spreading to Mainz, saw separatists form a provisional government with French support. However, the lack of recognition from the German Reich, local residents, and other Allied powers led to its failure. These episodes underscored the tensions between local identity and external governance during the occupation.[21] End of the occupation and National SocialismThe withdrawal of French troops in 1930 marked the end of a challenging decade for Mainz. However, the global economic crisis quickly eroded the brief economic recovery, with unemployment reaching 12.8% in 1932. This hardship fueled radical political movements, including the rise of the NSDAP. A local NSDAP branch, established in 1925, remained marginal until the early 1930s. By 1932, the party gained significant traction, receiving 26,186 votes in the state election. On 30 January 1933, the Nazi seizure of power was met with both opposition and celebration in Mainz: a Communist-led demonstration of 3,000 protested the takeover, while 700 NSDAP supporters marched in celebration.[22] The Nazi policy of Gleichschaltung (enforced conformity) transformed Mainz. Streets were renamed (e.g., Halleplatz to Adolf-Hitler-Platz), and the Liberation Monument on Schillerplatz was demolished. The city's Jewish community, numbering around 3,000, faced immediate persecution. The synagogues on Hindenburgstraße and in the Emmeransbezirk were destroyed during the Kristallnacht pogrom in November 1938, and most Jewish residents were deported during the Holocaust. A Torah scroll, hidden in the Mainz seminary, was rediscovered in 2003 and returned to the Jewish community in Weisenau. Political parties, trade unions, and the free press were banned, though the Catholic and Protestant churches in Mainz resisted Nazi co-optation, with figures like Bishops Ludwig Maria Hugo and Albert Stohr refusing cooperation. On 1 November 1938, Mainz became an independent city, incorporating Gonsenheim.[22] Second World WarThe Second World War initially had a limited impact on Mainz, with rationing and blackout measures as the primary disruptions. Cultural life, including theatre and cinema, continued to distract the population. The first bombs fell in 1940, followed by significant raids in 1941 targeting the city districts and the main railway station. The most destructive attack occurred on 12 August 1942, when British bombers dropped 134 tonnes of incendiary bombs and 203 tonnes of high-explosive bombs, devastating the Quintinsviertel district and destroying the collegiate church of St. Stephan. The attack, followed by another the next day, killed 161 people and destroyed numerous buildings.[22] The deadliest raid occurred on 27 February 1945, when the British Royal Air Force dropped 514,000 incendiary bombs, 235 high-explosive bombs, and 484 air mines in just 15 minutes, creating a firestorm that killed approximately 1,200 people, including the Capuchin nuns' convent. This date remains a central day of remembrance in Mainz. By March 1945, as American troops approached, the Wehrmacht destroyed all Rhine bridges in Mainz. On 22 March 1945, the 90th Infantry Division captured the city, ending the war for Mainz. Of the 154,000 residents in 1939, only 76,000 remained, with 61% of buildings destroyed (80% in the city centre). The Jewish community was reduced to just 59 members by 1945.[22] Post-war periodNew administrationsThe Yalta Conference in February 1945 assigned Mainz to the French occupation zone. After American forces captured the city in March 1945, French troops entered on 9 July 1945, marking their sixth occupation since 1644. The French designated Mainz as a key administrative centre, but the city faced significant challenges, including 1.5 million cubic meters of rubble and a severe shortage of workers. Economic hardship and hunger persisted, compounded by negotiations to limit the French dismantling of infrastructure. The separation of Mainz's right-bank districts (Kastel and Kostheim) from Wiesbaden reduced the city's area by more than half, a loss that remains unresolved.[23] University townDespite post-war difficulties, Mayor Emil Kraus announced the re-establishment of a university on 31 December 1945. The French, seeking to establish a university in their zone, chose Mainz over Speyer and Trier. The Johannes Gutenberg University was authorised to resume operations on 27 February 1946, exactly one year after the devastating bombing, using minimally damaged anti-aircraft barracks near the main cemetery. The university's founding, though controversial due to resource constraints, marked a step toward cultural and intellectual recovery. The Mainz Carnival resumed in 1946, and by 1948, the Catholic Day attracted 180,000 visitors, signalling a return to normalcy.[23] State capitalOn 30 August 1946, the French established Rhineland-Palatinate with Mainz as its capital, a decision celebrated with military ceremonies and a torchlight procession. The state government initially operated from Koblenz due to Mainz's war-damaged infrastructure, leading to a "capital dispute" between the two cities. By 16 May 1950, the state parliament voted to relocate to Mainz, and by May 1951, all ministries and the parliament were housed in the Deutschhaus, solidifying Mainz's role as the state capital.[23] Federal RepublicThe establishment of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949 marked the beginning of Mainz's economic recovery. The relocation of companies like Schott AG from Jena created 12,000 jobs by the late 1950s. However, reconstruction progressed slowly, with war damage visible into the 1970s. Urban planner Ernst May developed a general city plan in 1961, guiding rebuilding efforts. By the early 1960s, 19,000 apartments and key infrastructure were restored. The 1962 bicentennial celebration of Mogontiacum's founding highlighted Mainz's Roman heritage, with events showcasing archaeological sites like the Jupiter Column. The state gifted 62 hectares of land near Ober-Olmer Forest, leading to the development of the Lerchenberg district, where ZDF established its headquarters in 1963. The incorporation of Finthen, Drais, Hechtsheim, Ebersheim, and Laubenheim in 1969 doubled the city's area to 9,564 hectares, fostering growth.[23] Under Mayor Jockel Fuchs (elected 1965), Mainz saw significant development, including the establishment of the Hilton Hotel and IBM, which brought 3,000 jobs. The new town hall, designed by Arne Jacobsen, was inaugurated in 1973, alongside the Rheingoldhalle and the "Am Brand" shopping centre. The pedestrianisation of cathedral squares like Liebfrauenplatz in 1973 restored the historic city centre. Visits by international leaders, including Queen Elizabeth II (1978), Pope John Paul II (1980), and US Presidents George H. W. Bush (1989) and George W. Bush (2005), underscored Mainz's growing prominence.[23] 21st centuryThe year 2000 was celebrated as the Gutenberg Year, with Johannes Gutenberg named "Man of the Millennium" by TIME. The inaugural Gutenberg Marathon highlighted the city's cultural heritage. In 2004, 1. FSV Mainz 05, under coach Jürgen Klopp, achieved promotion to the Bundesliga, moving to a new stadium in 2009. Artistic cyclists Katrin Schultheis and Sandra Sprinkmeier won multiple world championships between 2007 and 2014.[24] The New Synagogue was inaugurated in 2010, symbolising the revival of the Jewish community. In 2011, Mainz was named the "City of Science," reflecting the contributions of the Johannes Gutenberg University. The customs and inland port relocated to Ingelheimer Aue, enabling a new residential and service district in Neustadt. The Mainzelbahn tram line opened in 2016, connecting the main station to Lerchenberg. In 2017, Mainz hosted the German Unity Day celebrations under the motto "Together we are Germany." A 2018 referendum rejected a proposed "Bible Tower" extension to the Gutenberg Museum, with low voter turnout. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Mainz-based BioNTech developed the BNT162b2 vaccine, with Schott Pharma producing pharmaceutical tubing for vials. The pandemic reduced particulate matter pollution, and a 30 km/h speed limit was introduced in the city centre in 2020 to further lower emissions. In 2021, the Jewish cultural heritage of Mainz, Speyer, and Worms (SchUM cities) was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, celebrated by Federal President Frank-Walter Steinmeier in 2023. In 2022, Belgium's King Philippe and Queen Mathilde visited Mainz, touring BioNTech and the Gutenberg Museum. In 2023, Nino Haase was elected Lord Mayor, ending 74 years of SPD leadership. The "Rhine Riverbank Framework Plan" was approved to redesign the Rhine riverbank, unsealing 6,000 square meters and creating green spaces. As of September 2025, Mainz, with a population of approximately 220,000, remains a vibrant state capital. The Mainz Carnival continues to thrive, drawing thousands annually, while the city's Roman, medieval, and Baroque heritage attracts tourists. The Johannes Gutenberg University and companies like BioNTech and Schott AG drive innovation, and ongoing urban projects balance historical preservation with modern sustainability, ensuring Mainz's continued significance in Rhineland-Palatinate and beyond.[24] References

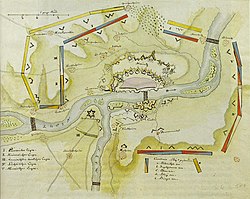

|