Gender equality

Gender equality, also known as sexual equality, gender egalitarianism, or equality of the sexes, is the state of equal ease of access to resources and opportunities regardless of gender, including economic participation and decision-making, and the state of valuing different behaviors, aspirations, and needs equally, also regardless of gender.[1] Gender equality is a core human rights that guarantees fair treatment, opportunities, and conditions for everyone, regardless of gender. It supports the idea that both men and women are equally valued for their similarities and differences, encouraging collaboration across all areas of life. Achieving equality doesn't mean erasing distinctions between genders, but rather ensuring that roles, rights, and chances in life are not dictated by whether someone is male or female. The United Nations emphasizes that gender equality must be firmly upheld through the following key principles: Inclusive participation: Both men and women should have the right to serve in any role within the UN's main and supporting bodies. Fair compensation: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights affirms that gender should never be a factor in pay disparities—equal work deserves equal pay. Balanced power dynamics: Authority and influence should be shared equally between genders. Equal access to opportunities: Everyone, regardless of gender, should have the same chances to pursue education, healthcare, financial independence, and personal goals. Women's empowerment: Women must be supported in taking control of their lives and asserting their rights as equal members of society. UNICEF (an agency of the United Nations) defines gender equality as "women and men, and girls and boys, enjoy the same rights, resources, opportunities and protections. It does not require that girls and boys, or women and men, be the same, or that they be treated exactly alike."[2][a] As of 2017,[update] gender equality is the fifth of seventeen sustainable development goals (SDG 5) of the United Nations; gender equality has not incorporated the proposition of genders besides women and men, or gender identities outside of the gender binary. Gender inequality is measured annually by the United Nations Development Programme's Human Development Reports. Gender equality can refer to equal opportunities or formal equality based on gender or refer to equal representation or equality of outcomes for gender, also called substantive equality.[3] Gender equality is the goal, while gender neutrality and gender equity are practices and ways of thinking that help achieve the goal. Gender parity, which is used to measure gender balance in a given situation, can aid in achieving substantive gender equality but is not the goal in and of itself. Gender equality is strongly tied to women's rights, and often requires policy changes. On a global scale, achieving gender equality also requires eliminating harmful practices against women and girls, including sex trafficking, femicide, wartime sexual violence, gender wage gap,[4] and other oppression tactics. UNFPA stated that "despite many international agreements affirming their human rights, women are still much more likely than men to be poor and illiterate. They have less access to property ownership, credit, training, and employment. This partly stems from the archaic stereotypes of women being labeled as child-bearers and homemakers, rather than the breadwinners of the family.[5] They are far less likely than men to be politically active and far more likely to be victims of domestic violence."[6] HistoryChristine de Pizan, an early advocate for gender equality, states in her 1405 book The Book of the City of Ladies that the oppression of women is founded on irrational prejudice, pointing out numerous advances in society probably created by women.[7][8] ShakersThe Shakers, an evangelical group, which practiced segregation of the sexes and strict celibacy, were early practitioners of gender equality. They branched off from a Quaker community in the north-west of England before emigrating to America in 1774. In America, the head of the Shakers' central ministry in 1788, Joseph Meacham, had a revelation that the sexes should be equal. He then brought Lucy Wright into the ministry as his female counterpart, and together they restructured the society to balance the rights of the sexes. Meacham and Wright established leadership teams where each elder, who dealt with the men's spiritual welfare, was partnered with an eldress, who did the same for women. Each deacon was partnered with a deaconess. Men had oversight of men; women had oversight of women. Women lived with women; men lived with men. In Shaker society, a woman did not have to be controlled or owned by any man. After Meacham's death in 1796, Wright became the head of the Shaker ministry until her death in 1821. Shakers maintained the same pattern of gender-balanced leadership for more than 200 years. They also promoted equality by working together with other women's rights advocates. In 1859, Shaker Elder Frederick Evans stated their beliefs forcefully, writing that Shakers were "the first to disenthrall woman from the condition of vassalage to which all other religious systems (more or less) consign her, and to secure to her those just and equal rights with man that, by her similarity to him in organization and faculties, both God and nature would seem to demand".[9] Evans and his counterpart, Eldress Antoinette Doolittle, joined women's rights advocates on speakers' platforms throughout the northeastern U.S. in the 1870s. A visitor to the Shakers wrote in 1875:

The Shakers were more than a radical religious sect on the fringes of American society; they put equality of the sexes into practice. It has been argued that they demonstrated that gender equality was achievable and how to achieve it.[11] Suffrage movementIn wider society, the movement towards gender equality began with the suffrage movement in Western cultures in the late-19th century, which sought to allow women to vote and hold elected office. This period also witnessed significant changes to women's property rights, particularly in relation to their marital status. (See for example, Married Women's Property Act 1882.) Early Soviet UnionStarting in 1927 the Communist Party of the Soviet Union enforced gender equality within Soviet Central Asia during Hujum campaign.[12] Post-war eraSince World War II, the women's liberation movement and feminism have created a general movement towards recognition of women's rights. The United Nations and other international agencies have adopted several conventions which promote gender equality. These conventions have not been uniformly adopted by all countries, and include:

Such legislation and affirmative action policies have been critical to bringing changes in societal attitudes. A 2015 Pew Research Center survey of citizens in 38 countries found that majorities in 37 of those 38 countries said that gender equality is at least "somewhat important", and a global median of 65% believe it is "very important" that women have the same rights as men.[18] Most occupations are now equally available to men and women, in many countries.[i] Similarly, men are increasingly working in occupations which in previous generations had been considered women's work, such as nursing, cleaning and child care. In domestic situations, the role of Parenting or child rearing is more commonly shared or not as widely considered to be an exclusively female role, so that women may be free to pursue a career after childbirth. For further information, see Shared earning/shared parenting marriage. Another manifestation of the change in social attitudes is the non-automatic taking by a woman of her husband's surname on marriage.[19] A highly contentious issue relating to gender equality is the role of women in religiously orientated societies.[ii][iii] Some Christians or Muslims believe in Complementarianism, a view that holds that men and women have different but complementing roles. This view may be in opposition to the views and goals of gender equality.  In addition, there are also non-Western countries of low religiosity where the contention surrounding gender equality remains. In China, a cultural preference for a male child has resulted in a shortfall of women in the population. The feminist movement in Japan has made many strides which resulted in the Gender Equality Bureau, but Japan still remains low in gender equality compared to other industrialized nations.Developing countries like Kenya, on the other hand, do not have official national statistics and have to rely on some gender-disaggregated statistics, usually funded by international organizations, for their analysis.[20] The notion of gender equality, and of its degree of achievement in a certain country, is very complex because there are countries that have a history of a high level of gender equality in certain areas of life but not in other areas.[iv][v] Indeed, there is a need for caution when categorizing countries by the level of gender equality that they have achieved.[21] According to Mala Htun and S. Laurel Weldon "gender policy is not one issue but many" and:[22]

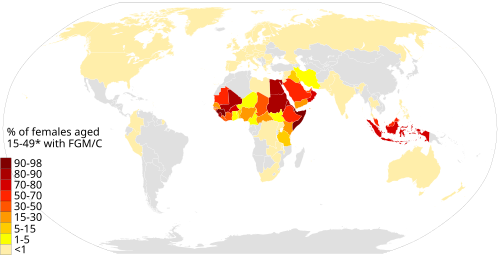

Not all beliefs relating to gender equality have been popularly adopted. For example, topfreedom, the right to be bare breasted in public, frequently applies only to males and has remained a marginal issue. Breastfeeding in public is now more commonly tolerated, especially in semi-private places such as restaurants.[23] United NationsIt is the vision that men and women should be treated equally in social, economic and all other aspects of society, and to not be discriminated against on the basis of their gender.[vi] Gender equality is one of the objectives of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[24] World bodies have defined gender equality in terms of human rights, especially women's rights, and economic development.[25][26] The United Nation's Millennium Development Goals Report states that their goal is to "achieve gender equality and the empowerment of women". Despite economic struggles in developing countries, the United Nations is still trying to promote gender equality, as well as help create a sustainable living environment is all its nations. Their goals also include giving women who work certain full-time jobs equal pay to the men with the same job. Contemporary efforts to fight inequalityEuropean Union InitiativesThe European Union has taken significant steps to institutionalize gender equality efforts. In 2010, the European Union opened the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) in Vilnius, Lithuania to promote gender equality and to fight sex discrimination.[27] Building on its gender equality agenda, the EU in 2015 adopted a comprehensive Gender Action Plan for 2016–2020.[28] This was followed by a third Gender Action Plan covering 2020–2025 (GAP III), introduced in late 2020 with the aim of accelerating progress on empowering women and girls and safeguarding the gains made in gender equality.[27][29] National Education and Policy InitiativesGender equality is part of the national curriculum in Great Britain and many other European countries with other subjects like Personal, social, health and economic education, religious studies and language acquisition addressing gender issues as serious topics for discussion and societal analysis. In Central Asia, the Republic of Kazakhstan undertook a decade-long Strategy for Gender Equality 2006–2016 by presidential decree to advance women's status and opportunities .[30] Following that period, Kazakhstan introduced a new "Concept for Family and Gender Policy until 2030" in 2017 as a national roadmap to further gender equality goalsebrd.com. This updated strategy, supported by government and international partners, continues Kazakhstan's efforts to enhance women's rights and participation in all sectors of society.[31] Legal Reforms for Women's RightsIn the Philippines, a landmark law known as the Magna Carta of Women (Republic Act No. 9710) was signed in August 14, 2009 by then-President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. This comprehensive law affirms women's rights as human rights and seeks to eliminate all forms of discrimination against women. The Magna Carta of Women compiles and strengthens existing human rights provisions for women, mandates equal opportunities for women in all spheres, and aligns with international conventions such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). It also requires that women be able to participate in policy formulation, planning, and decision-making processes for programs and services, thereby ensuring that women have a voice in governance and development.[32] Gender Equality, Health, and Development ProgramsA large and growing body of research has shown that gender inequality negatively impacts health outcomes and hinders social and economic development. In response, international organizations emphasize comprehensive empowerment strategies for women and girls. The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) states that advancing women's empowerment and gender equality requires strategic interventions at all levels of programming and policy-making, including in reproductive health, economic opportunity, education, and political participation.[33] In other words, improving gender equality involves multisector efforts; from ensuring access to healthcare and family planning, to expanding women's economic resources and decision-making power, to boosting girls' educational attainment and leadership roles.UNFPA says that "research has also demonstrated how working with men and boys as well as women and girls to promote gender equality contributes to achieving health and development outcomes."[34] T hese findings have informed programs worldwide that involve men as partners in challenging gender norms—such as initiatives encouraging fathers' involvement in maternal health, or boys' education programs about equality and respect—as a means to create more sustainable and inclusive progress toward gender equity. Overall, the health and development sectors increasingly recognize gender equality not only as a fundamental human right but also as a prerequisite for broader societal well-being. Gender-Responsive Policies and AgricultureIn the past decade, many countries have made improvements in integrating gender considerations into national policy frameworks, though progress is uneven across sectors. Governments in regions like East Africa and Latin America have increasingly acknowledged structural gender gaps - such as unequal access to land, agricultural inputs, finance, and technology for women and have begun crafting policies and budgets to produce more gender-responsive outcomes.[35] However, the degree to which such policies explicitly prioritize gender equality and women's empowerment varies widely.[35] A comprehensive analysis by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) illustrates this variability in the agricultural sector. The FAO reviewed agricultural policy documents from 68 countries and found that while over 75% of these policies recognized the roles of women or the challenges they face in agriculture, only 19% set gender equality in agriculture or women's rights as clear policy objectives, and a mere 13% explicitly encouraged the participation of rural women in the policy-making process.[35][36] Most countries acknowledge women's contributions to agriculture, but far fewer translate that recognition into concrete goals or inclusive decision-making structures for women. Global Acceleration InitiativesIn recent years, global partnerships and action plans have been launched to accelerate progress toward gender parity. Notably, in 2021 the Generation Equality Forum convened by UN Women and co-hosted by the governments of Mexico and France became a major international effort to catalyze gender equality efforts. The Forum culminated in Paris in July 2021 with the announcement of a Global Acceleration Plan for Gender Equality and nearly USD 40 billion in pledged investments to advance women's rights.[37] This five-year action plan (running through 2026) mobilizes governments, civil society, and the private sector to tackle critical barriers to gender equality, from gender-based violence to economic and educational disparities. The timing of this initiative was significant: it arrived as the world was grappling with the COVID-19 pandemic, which disproportionately affected women and girls (through increased caregiving burdens, job losses, and gender-based violence during lockdowns). The Generation Equality commitments thus also emphasized gender-responsive recovery measures so that women and girls are not left behind in post-pandemic rebuilding.[37] Through its six Action Coalitions and a Compact on Women, Peace and Security, the Forum outlined concrete targets – for example, improving women's economic opportunities, ending violence against women, and promoting women's leadership in climate action – to be achieved by 2026. The Generation Equality Forum represents a renewed global resolve, 25 years after the landmark 1995 Beijing Conference, to inject resources and accountability into achieving gender equality within the current decade. Promoting Gender Equality in ScienceIn September 2020, a coalition of leading international scientific organizations established the Standing Committee for Gender Equality in Science (SCGES) as part of the follow-up to a project called "A Global Approach to the Gender Gap in Mathematical, Computing, and Natural Sciences." The SCGES was created to promote equal access for women and girls to science education and careers, and to coordinate global efforts in fostering gender equality within scientific fieldsgender-equality-in-science.org. This committee serves as an interdisciplinary network connecting scientific unions and societies, aimed at sharing best practices and developing joint strategies to reduce the gender gap in STEM disciplines. One of SCGES's key initiatives, in collaboration with the International Science Council (ISC), is a project titled "Women Scientists Around the World: Strategies for Gender Equality." This initiative is a series of articles based on interviews with women scientists across various disciplines and regions – many of whom have attained leadership positions in science – to explore the drivers of success, the challenges they have faced, and the strategies that can advance gender parity in scientific organizations. By documenting personal stories and qualitative insights from different countries, the series sheds light on persistent obstacles (such as bias, lack of support, or structural barriers) and highlights effective approaches to overcome them. The establishment of SCGES and its programs signifies a growing recognition that achieving gender equality in science requires targeted action, from mentoring and visibility for women scientists to policy changes within scientific institutions. These efforts complement broader gender equality campaigns, ensuring that progress includes the scientific and technical sectors which are crucial for innovation and development.[38] Health and safetyEffect of gender inequality on health Social constructs of gender (that is, cultural ideals of socially acceptable masculinity and femininity) often have a negative effect on health. The World Health Organization cites the example of women not being allowed to travel alone outside the home (to go to the hospital), and women being prevented by cultural norms to ask their husbands to use a condom, in cultures which simultaneously encourage male promiscuity, as social norms that harm women's health. Teenage boys suffering accidents due to social expectations of impressing their peers through risk taking, and men dying at much higher rate from lung cancer due to smoking, in cultures which link smoking to masculinity, are cited by the WHO as examples of gender norms negatively affecting men's health.[39] The World Health Organization has also stated that there is a strong connection between gender socialization and transmission and lack of adequate management of HIV/AIDS.[40]  Certain cultural practices, such as female genital mutilation (FGM), negatively affect women's health.[42] Female genital mutilation is the ritual cutting or removal of some or all of the external female genitalia. It is rooted in inequality between the sexes, and constitutes a form of discrimination against women.[42] The practice is found in Africa,[43] Asia, Middle East and Indonesia, and in Europe among immigrant communities from countries in which FGM is common. UNICEF estimated in 2016 that 200 million women have undergone the procedure.[44]  According to the World Health Organization, gender equality can improve men's health. The study shows that traditional notions of masculinity have a big impact on men's health. Among European men, non-communicable diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory illnesses, and diabetes, account for the vast majority of deaths of men aged 30–59 in Europe which are often linked to unhealthy diets, stress, substance abuse, and other habits, which the report connects to behaviors often stereotypically seen as masculine behaviors like heavy drinking and smoking. Traditional gender stereotypes that keep men in the role of breadwinner and systematic discrimination preventing women from equally contributing to their households and participating in the workforce can put additional stress on men, increasing their risk of health issues, and men bolstered by cultural norms tend to take more risks and engage in interpersonal violence more often than women, which could result in fatal injuries.[45][46][47][48] Violence against women   Violence against women (VAW) is a technical term used to collectively refer to violent acts that are primarily or exclusively committed against women.[vii] This type of violence is gender-based, meaning that the acts of violence are committed against women expressly because they are women, or as a result of patriarchal gender constructs.[viii] Violence and mistreatment of women in marriage has come to international attention during the past decades. This includes both violence committed inside marriage (domestic violence) as well as violence related to marriage customs and traditions (such as dowry, bride price, |